This story dates back to the 1970s when I was working as a lending officer in Rome. One of my tasks was to evaluate applications for small business loans in the Mezzogiorno, including the islands of Sardinia and Sicily. That was when I learned about the market for Sicilian oranges.

The different varieties were usually on display on the market stalls near our first apartment in Rome. Although it was almost fifty years ago, my memory tells me that the Moro is the darkest of the distinctively Sicilian blood oranges, with a ruby red juice, followed by the Tarrocco and the Sanguinello, each of them almost as round as a tennis ball. Others such as the Ovale are more like the Valencian oranges from Spain, with a juice that is typically orange in colour, and are just as likely to be grown in Calabria.

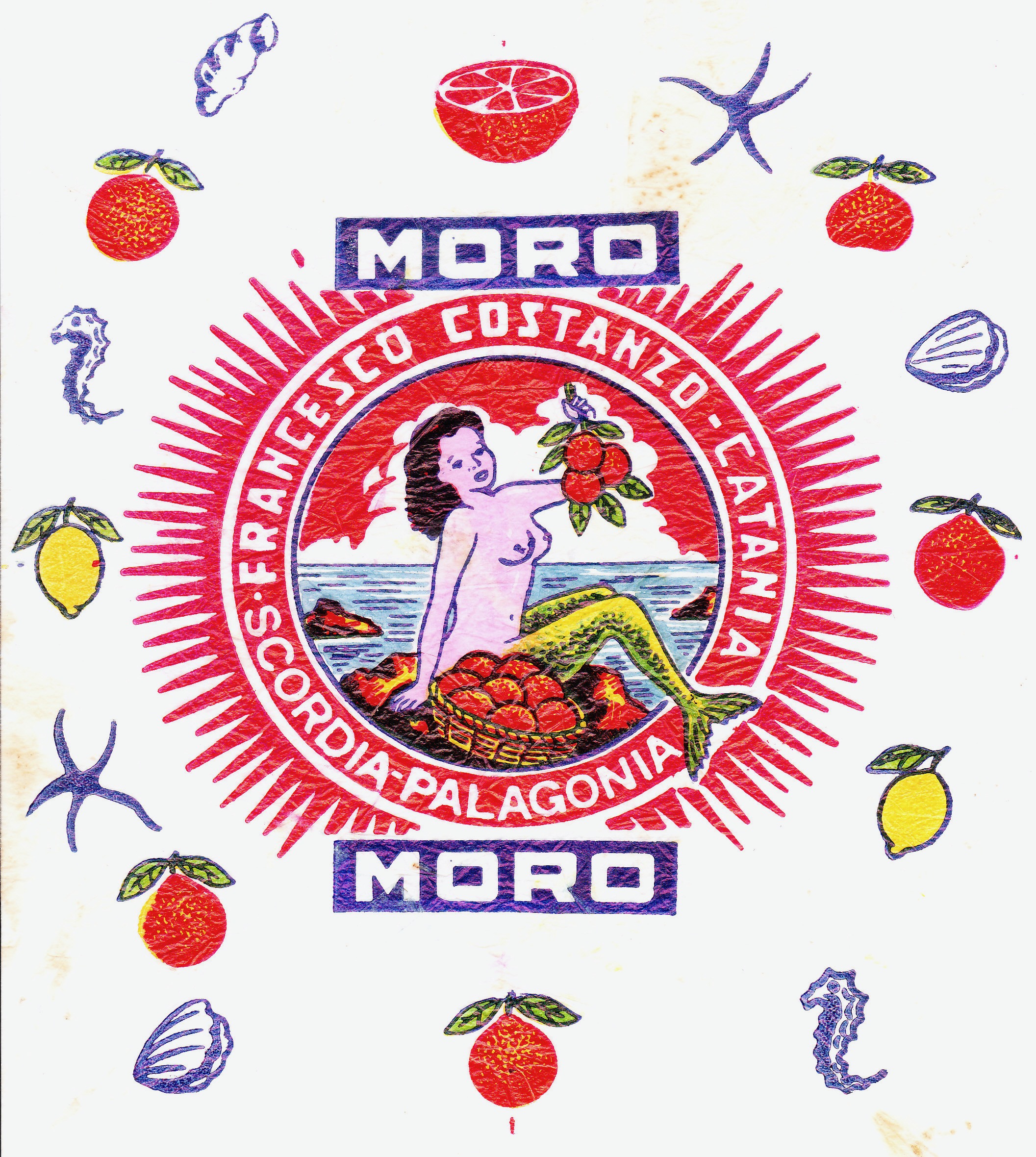

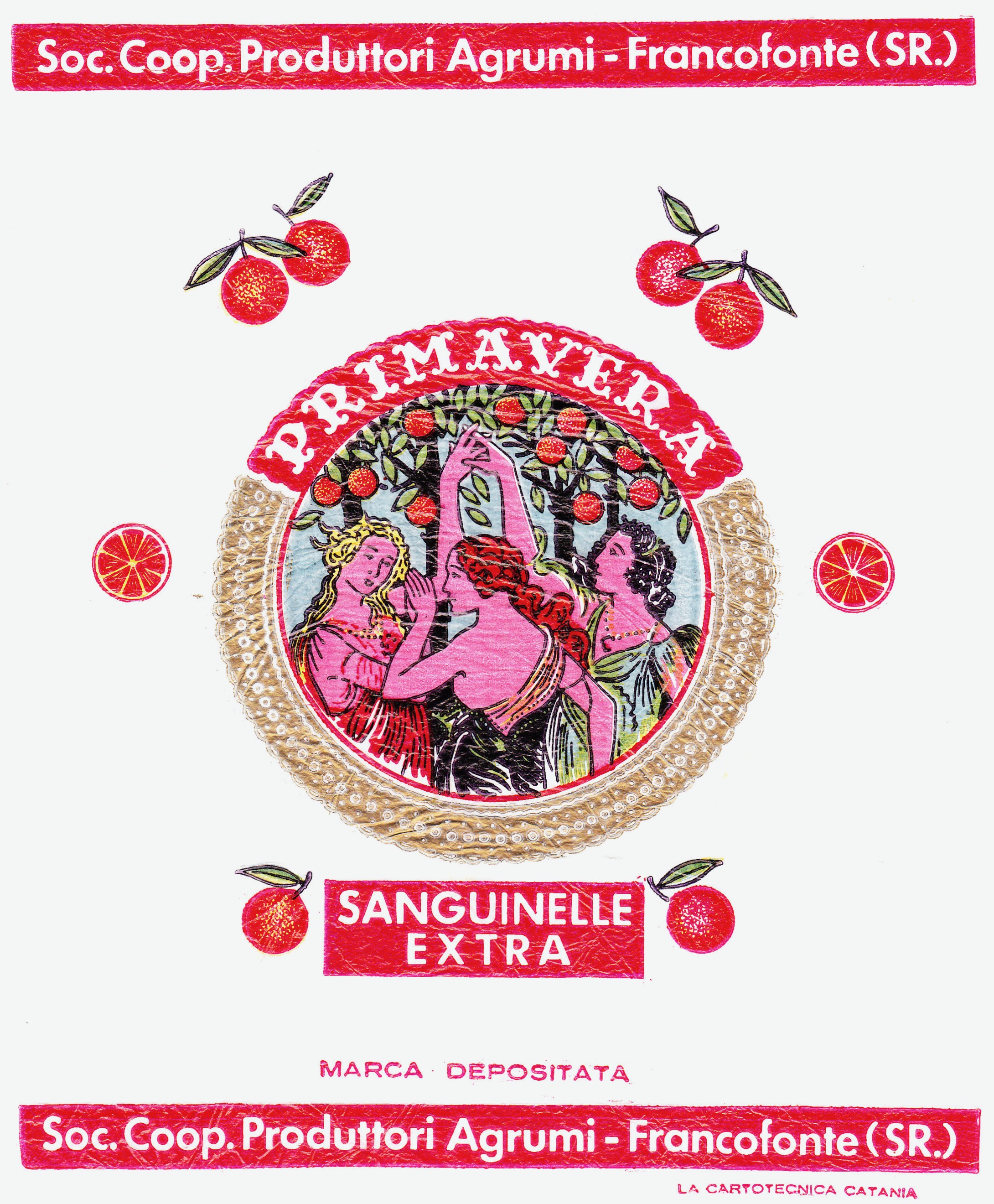

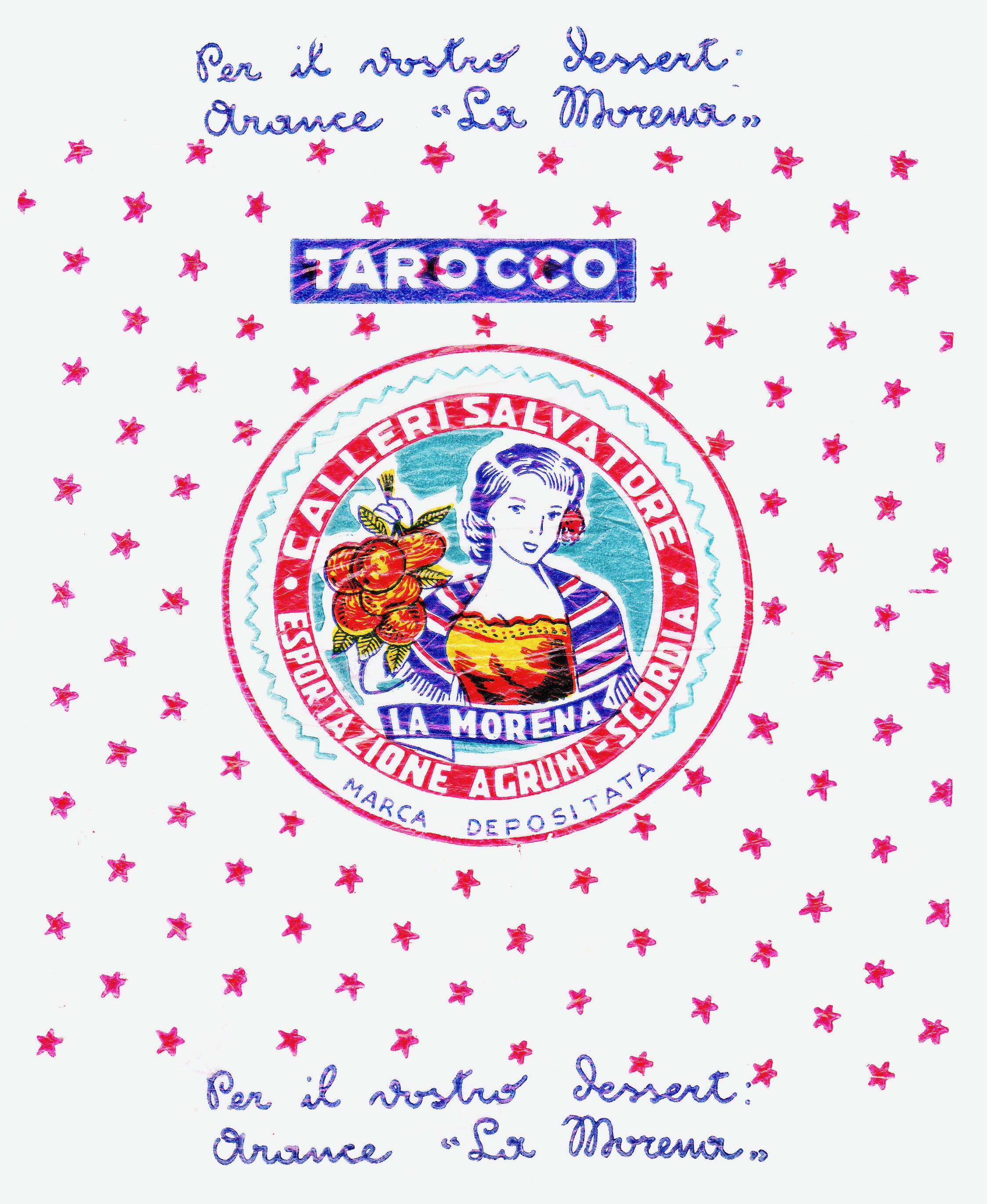

Sicilian oranges – Moro, Sanguinello, Tarrocco, Ovale

Two of these wrappers tell us a little about the market for oranges – they indicate the name of the grower-distributor: Francesco Costanzo, Scordia & Palagonia (Catania); Società Cooperativa Produttori Agrumi, Francofonte (Siracusa).

The trays of produce in the Rome markets were always a splendid sight. Each citrus fruit was wrapped carefully in a brightly decorated tissue paper, giving the required impression of quality and sometimes a clear indication of provenance, while at the same time affording protection from any mould that might have developed on another orange in the box since picking. That anyway was my understanding at the time.

As a rapporteur in a development bank, I had to prepare a recommendation on each project based not only on financial viability but also on economic impact. I had already reviewed proposals concerning the production of olive oil and wine by small firms in the Mezzogiorno, but this was the first and only application regarding the market for oranges. As we covered many areas of business activity, and did not work as sector specialists, informed evidence concerning the structure of the industry and its prospects was an obvious pre-requirement for each project analysis. But I soon ran into a problem – the proposal did not include a sufficiently detailed economic analysis of the citrus fruit industry in Sicily.

In most sectors at that time, trade statistics were made available by regional organisations that collected and consolidated data on output volumes. However, in addition to an understanding of the size of the sector and the expected growth in demand, which were documented in the submission, we also wanted confirmation that the wholesale market for oranges really was as fragmented as the proposal suggested, i.e. that the supply was still in the hands of countless small orchards, local cooperatives and family businesses. The project proposal was to create a distribution network that would revamp the export of the Sicilian orange harvest to the mainland, with better storage en route and improved transportation to major population centres. One rationale was that the new structure would bring the producers closer to the price that could be negotiated wholesale on the mainland – as a result, their cash flows would no longer be capped by pricing that was controlled closer to hand by various parties. This was where the politics and the economics of development would have to coalesce in order to fulfil our remit, which was to support the creation of new jobs in small firms in areas of relatively low average income.

THE THEORETICAL MARKET FOR LEMONS

As it happens, a theoretical market known as the market for lemons is well established in economics. When it was first thought through, the market for lemons described the pricing of potentially defective second-hand automobiles (‘lemons‘ in the American trade jargon). It was soon shown that the same thinking could be applied more generally to any product where the sellers have more information about quality than the buyers, some sales being made in good faith and others when the product is known by the seller to be unreliable. Without guarantees, warranties or prior inspection at an added cost, the rational price from a buyer’s perspective would be the average value of a dud product and a quality product, but this has the effect of driving quality products out of the market as they can only sell at a loss, and the market dries up.

At least, that is the theory at its simplest. The two concepts involved are known by economists as information asymmetry and adverse selection. Interestingly, although the market for lemons did not help me to understand the Sicilian market for oranges, it did explain my employer’s own market for credit. That is to say, given that the borrower in this case knew more about the Sicilian orange market than the lender (information asymmetry), and we in turn could not be sure that the project was worthwhile, these very circumstances could have resulted in the ‘bad’ driving out the ‘good’ (adverse selection). When banks find it difficult to identify risky businesses, they end up charging a higher rate of interest to everyone in order to compensate. The good businesses see their cost of debt rise unnecessarily as a result, and they are crowded out from the credit market. Furthermore, because the loan portfolio becomes riskier, the bank is likely to raise interest rates yet again and crowd out the good projects even more. This is how credit markets dry up as well.

THE REAL MARKET FOR ORANGES

My counterpart at the regional financial institution (the bank for local infrastructure funding) was unable to add much initially. That was understandable – he was a helpful man who probably had tried already to lay his hands on the extra information. He never actually replied with a “No” to any request but, if he really had to turn us down, he simply raised his head the smallest fraction and clicked quietly with his tongue, which by then I knew to be the traditional gesture in the South in such circumstances.

That weekend, Heather joined me in a bit of market research. We walked the length of the street market that stretched along Via Trionfale right down to the river, not far from the Vatican. We purchased two large bags of oranges in all, buying one at a time and stopping at a new stall whenever we spotted a different wrapper. I have kept the tissue papers all these years in a folder, and have dug them out again to write this up.

Interestingly, these are more than just wrappers – they provide a snapshot of Italian society, spanning aesthetic references, invocations of the past and allusions to the popular culture of the 1970s. Above, we can see that Botticelli’s Three Graces are the fruit pickers, and below it looks almost as though Gina Lollobrigida and Sophia Loren are out there picking as well. Above again, the voluptuous mermaid holding oranges is particularly dark-haired (moro in Italian), and back below there are moors from Africa (also moro in Italian), the more appropriate referent on these 1970s wrappers perhaps being the itinerant migrant workers from Africa who actually did some of the harvesting. Further on below, the leopard (il gattopardo) reminds us of the great Sicilian novelist Giuseppe Tomasi Di Lampedusa; the depicted horse is Ribot, the world’s outstanding postwar thoroughbred (Italian-sired and trained) that never lost a race; and the eagle looks back to an Imperial past. And there are other images to decipher, including the exotic birds that frequent the citrus orchards and the cartoon characters that define the period.

But the main aim at the time was simply to list as many of the firms involved in the industry as possible :-

Calleri Salvatore, Scordia (Catania); Filippo & Carmello Zuccarello, Palagonia (Catania).

Nicolai Renato & Antonio, Paterno (Catania); Pantò Salvatore di Antonio, Lentini (Siracusa).

Gaetano Costa, Villabate (Palermo); Ditta Fileti & Muscara, Lentini (Siracusa); Ditta Cosimo Parisi, Ali’Terme (Messina); P & C Magnano (Siracusa); Sebastiano Salinitri, Mascali (Catania); Greco & Cirando, Zigolo & Francofonte (Siracusa), Adrano, Palagonia & Scordia (Catania); Santangelo Gaetano, Paternò (Catania).

Fratelli di Stefano SpA (Catania); Ditta Pietro Santo F. Attilio & Figlio, Lentini & Fondi (Siracusa), Paternò (Catania); Carlo Palermo & C., Francofonte (Siracusa)

Ditta Nolfo Francesca, Scordia (Catania); Antonio Cantarella (Catania); Ditta Farinato & Bua, Adrano (Catania).

Giuseppe Alba, Scordia & Palagonia (Catania); Giuseppe Sciré, Scordia (Catania).

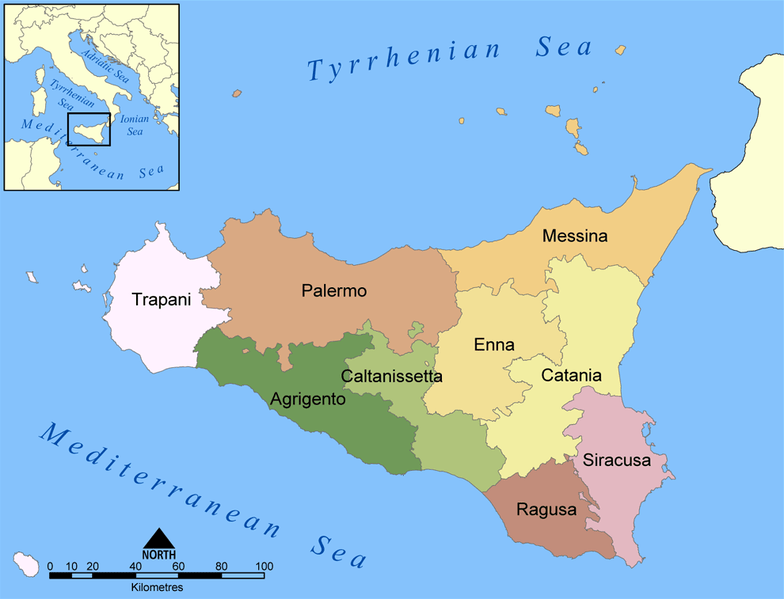

It turns out that the small sample was fairly representative. The Sicilian blood oranges are grown predominantly in the Catania province, many within sight of the Etna volcano, and some in the province of Siracusa. Of course, other types of orange that are grown in Sicily may have their provenance in other parts of the island, and some of the firms selling in Rome may have been distributing agents rather than producers, centred on the large ports in Palermo and Messina.

This map shows the provinces of Sicily.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

FINALLY..

A Saturday stroll through the Mercato Trionfale (which was then an open street market) was clearly not the most robust research approach that I could have used, but it was surprisingly effective nevertheless! Our friends at the regional bank quickly rose to the challenge and forwarded a more comprehensive analysis, and eventually the changes to the market for Sicilian oranges went ahead.

More:

Lisa Schultz, Unwrapping the Golden Apple – A Colorful History Of Orange Wrappers, The New Gastronome

INCARTI DI ARANCE / ORANGE WRAPPERS / PAPIERS D’ORANGE, Facebook group administered by Romana Gardani (see also www.nonsoloarance.net)

Leave a comment