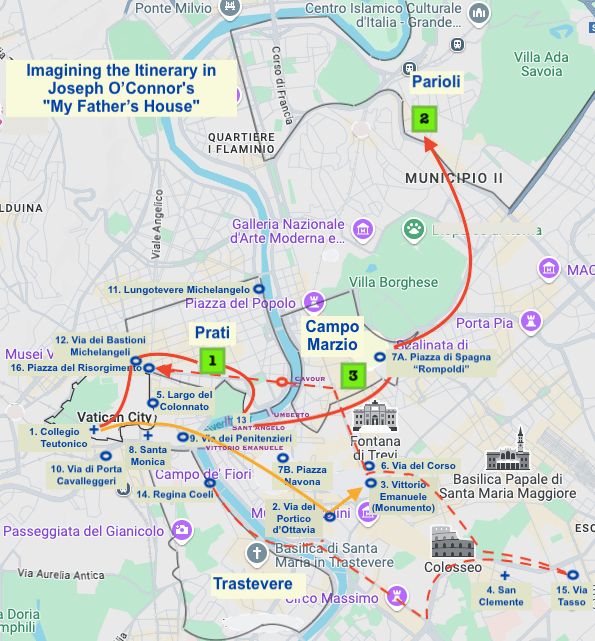

Before the occupation of Rome in the second world war, Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty would take the occasional brisk walk across the city from his residence in the Vatican’s Collegio Teutonico (1). On hot days, he would stop for an orange juice at a bar on the Via del Portico d’Ottavia (2) and then carry on a short distance to the Vittorio Emanuele monument (3) before returning home. I have drawn this route onto the annotated (contemporary) map below with an orange line.

Hugh is an administrative cleric in the Curia, formerly a priest, and still at heart an affable Kerry man. On the side, he has another and quite different mission – Hugh is the co-ordinator of a clandestine escape network operating from within the neutral Vatican City, helping Allied prisoners of war to avoid recapture and to leave the country, and assisting Jewish refugees to flee as well.

After six months’ confinement to the Vatican enclave for disregarding neutrality obligations while visiting POW camps, Hugh volunteers to attend the friary of San Clemente (4) on the other side of the city, where he helps with confession. It is September 1943, just a few days after the Nazi occupation of Rome and Mussolini’s relocation to Salò as the head of the new puppet government, as well as the Allied landings on the toe of Italy.

Hugh is already on the Gestapo watch list, and he comes to their attention once again en route to the friary by intervening when a Jewish couple are harassed.

While the historical lens is broadly authentic, the reader who looks for spatial credibility may be tempted to filter through the amalgamation of real streets, imagined streets and those coded by number. For instance, it turns out that some of the bluffs are thoroughfare names borrowed from Genova, Naples and elsewhere. As for the coded street names, such as Via Diccianove (19) and Via Segundo (2nd), it comes to mind that cities and towns throughout Italy tend to use the dates of important historical events for prominent roads, starting therefore with a number, e.g. Via 24 Maggio (the outbreak of war with Austria in 1915), Via 22 Settembre (the arrival of the forces of the Risorgimento in Rome in 1870). However, this is an unfortunate red herring of my own construction and has not helped to crack the code! In this attempt to unravel the itinerary that is suggested by the plot, I have picked out (and highlighted here in bold) a good number of recognisably genuine locations within the eternal city (where we had the good fortune to live in the 1970s).

The story unfolds in a nonlinear manner. Early on, we hear from Delia Kiernan, an Irish ballad singer who is married to the diplomatic head of Ireland’s Mission to the Holy See. It is mid-December in 1943, and Delia and Hugh are transporting a man to hospital in her car, surprisingly successfully given that her diplomatic immunity means very little to the occupying Nazis. The man is Sam Derry, a British officer who has himself escaped from an Italian camp and is now in hiding underneath the Vatican, and a key member of the group supporting the escape line.

We also hear from: Enzo Angelucci who runs a newspaper kiosk at the corner of Largo del Colonnato (5) on the edge of St Peter’s square; the Contessa Giovanna Landini who owns one of the majestic town houses that are hidden behind plain walls on the Via del Corso (6); and a Swiss journalist, the daughter of Dutch parents, by the name of Marianna de Vries. Before the occupation, Marianna would have long lunches with Hugh at the presumably apocryphal “Rompoldi” bar in the Piazza di Spagna (7A), plus the odd cappuccino in the Piazza Navona (7B).

Lastly, we meet the two remaining members of the impromptu “choir,” whose rehearsals are the ruse for escape line meetings. They are Sir Francis D’Arcy Osborne, scion of Haileybury College and now the British ambassador to the Holy See, and his trusty jack-of-all-trades John May, who together have retreated to the British legation’s offices within the Vatican walls. The Toff and his Cockney dogsbody may be stock characters, but reading John May’s recollection of events is as if my great uncles and aunts from Bethnal Green and Holloway Road were back with us again, speakin’ as proper Londoners would back then. The author has a great ear for the tempo of speech and the distinctive turn of phrase.

Giovanna and Marianna are in attendance when Hugh gives a sermon at the church of Santa Monica (8), next to St Peter’s and close to the spot where Giovanna and Hugh later make contact in full view of the Gestapo. As there are severe restrictions on movement into and out of the Vatican, Hugh approaches the border line nervously over Vatican cobbles as the Contessa strikes up conversation with him from the Rome side, fearlessly in her case.

When Giovanna Landini walks away towards the Via dei Penitenzieri (9), I started to worry that she might be picked up and tortured, spilling the beans on the whole set-up. Joseph O’Connor certainly knows how to stir up these suspicious (and ungracious) thoughts in the reader’s mind, generating new story lines that are not in the book but which are somehow latent. Initially, I wondered if the work might prove to be a fantasy, albeit told with Joycean flair, but that really is unfair as – quite to the contrary – the underlying story is factually based and some of the characters genuinely larger than life, indeed heroically so at the time (see Hugh, Sam, Delia, Francis).

On Christmas Eve of 1943, the money needed to smooth the passage of the next set of escapees is to be dropped in three locations across Rome, (i) not far from the Vatican in Prati, (ii) further afield in Parioli, and (iii) in Campo Marzio close to the historical centre. The codename for this operation is the RENDIMENTO, which in day-to-day Italian mostly refers to “economic yield” and sometimes to “thanksgiving” although here the connotation seems to be “performative action” (one that is rendered, maybe).

The night of the Rendimento starts when the switch is thrown on searchlights that are mounted on the roof of a hotel in the Via di Porta Cavallegerri (10), illuminating the southern approaches to the Vatican throughout the night.

Hugh and Sam receive intelligence about the nearby bridges over the Tiber, that the Ponte Cavour is likely to be barricaded, the Ponte Sant’Angelo left unguarded and certain roads blocked. When testing Enzo to see if he is ready to carry out the drop in place of the still-recovering Sam, Enzo is asked how he would handle matters if the Gestapo chief Hauptman were to stop him on the highway that runs alongside the Tiber (“Tevere” in Italian), on the stretch that is known as Lungotevere Michelangelo (11). Enzo’s answers seem to be quite carefree and he is not selected.

Taking the task on himself, Hugh makes his way through Vatican passageways to the north corner of the Papal territory where he emerges onto the Via dei Bastioni Michelangeli (12), outside the museum. After dropping the first wad of bank notes in Prati, Hugh carries on towards the Ponte Sant’Angelo. As he approaches he can see that the tip off was wrong, maybe deliberately misleading – there are tanks on the bridge, and the Ponte Umberto and Ponte Vittorio Emanuele are blocked off as well.

Hugh is not the sort to throw in the towel and return home, so instead he goes down to the quayside where he almost bumps straight into a couple of soldiers. Luckily – but unknown to Hugh – John May has him covered, soon picking him up in a purloined skiff and ferrying him over the river (13). Hugh then heads towards Parioli, passing through one of the tourist haunts where he has a nasty fall. Struggling on, he drops the second bundle through a coal hole on the edge of the Parioli district, where Marianna lives, and where she is waiting to assist with the onward distribution.

The red line on the contemporary map gives a possible route from the exit by the Vatican museum to drop no. [1] in Prati and then to drop no. [2] in Parioli. Needless to say, the itinerary in the book is not so much of a beeline, more a zig-zag of alleyways and back streets. The precise drop locations are taken from the detailed map of Rome that is included by the author at the front of My Father’s House, while the potential route imagined here is based on pointers gleaned from the story itself. For example, “to his right .. the Ponte Vittorio Emanuele” and “the Ponte Umberto .. a few hundred metres to his left” help to pinpoint the spot where Hugh was picked up by John May in the skiff.

On the next stretch, after the Parioli drop, we find Hugh crouching behind some bins while five bulldozers roar past along the quayside. He is evidently by the river again – but whereabouts in the city? The next time we see him, Hugh is picking his way across a bomb site when he is harried by one of the local fascisti. Luck is with him once again as the “choir” is still keeping an eye out for Hugh – Enzo Angelucci magically appears and floors the other man. Unfortunately, three of the occupying force’s conscripts arrive at the scene and Enzo flees. The three then escort Hugh to his supposed destination, and he leads them to the apartment that Delia has moved into with her daughter Blon for Christmas. After a bit more trickery, Hugh is able to escape and he apparently heads northwards from Delia’s flat. Hauptman hears from the escort that Hugh is on the loose, and that he is making for the area of Trastevere.

In the meantime, Hugh passes a Franciscan cemetery, crosses train tracks and walks along the coded Via 29. We know already that the third drop will be in Campo Marzio, but this step in the Rendimento is even more furtive than before, too cloak-and-dagger to be able to map, involving a hooded car journey on the way there and a blindfolded one afterwards.

When Hugh gets out of the car for the second time, with all three drops completed successfully, he is once again by the Tiber where he can see St Peter’s across the rooftops. He gets as far as an unnamed prison on the banks of the Tiber, presumably the Regina Coeli (14), which is in the Trastevere district and not far from the Vatican. It is here where Hugh finally falls into Gestapo hands, those of Hauptman himself, who takes him ominously to their headquarters in the Via Tasso (15). At the last minute, the Monsignor is able to commandeer Hauptman’s Mercedes, and he drives it at breakneck speed across Rome to the Ponte Cavour. Given the guards’ great fear of their commandant, Hauptman, they are reluctant to shoot at his car in case their orders are misguided. Hugh hurtles across the bridge towards his pre-arranged Rendimento rendez-vous, where Giovanna is waiting with motor bike that takes him the remaining distance through alleyways and back streets to the Piazza del Risorgimento (16), right by the Vatican. This final stage is mapped above with a dotted red line.

The thriller ends with a very neat moral dilemma when, at a later date, the gaoled Hauptman asks Hugh to receive him formally into the Catholic faith. Should he go ahead, or should he refuse? This is a book filled with unexpected turns of event, and skilfully crafted.

To me, the unresolved puzzle in My Father’s House is how the events surrounding drop no. [3] fit together on the map of Rome. But should they? The book is after all a creative tour de force. As the author explains in the concluding Caveat: “While real people and real events inspired the work of fiction that is My Father’s House, it is first and last a novel. Liberties have been taken with facts, characterisations and chronologies.” Nonetheless, while most published reviews of this book have searched out the true characters and events, this synopsis has been something of a quest for the true locations.

Stuart McLeay, 20th November 2024

Leave a comment