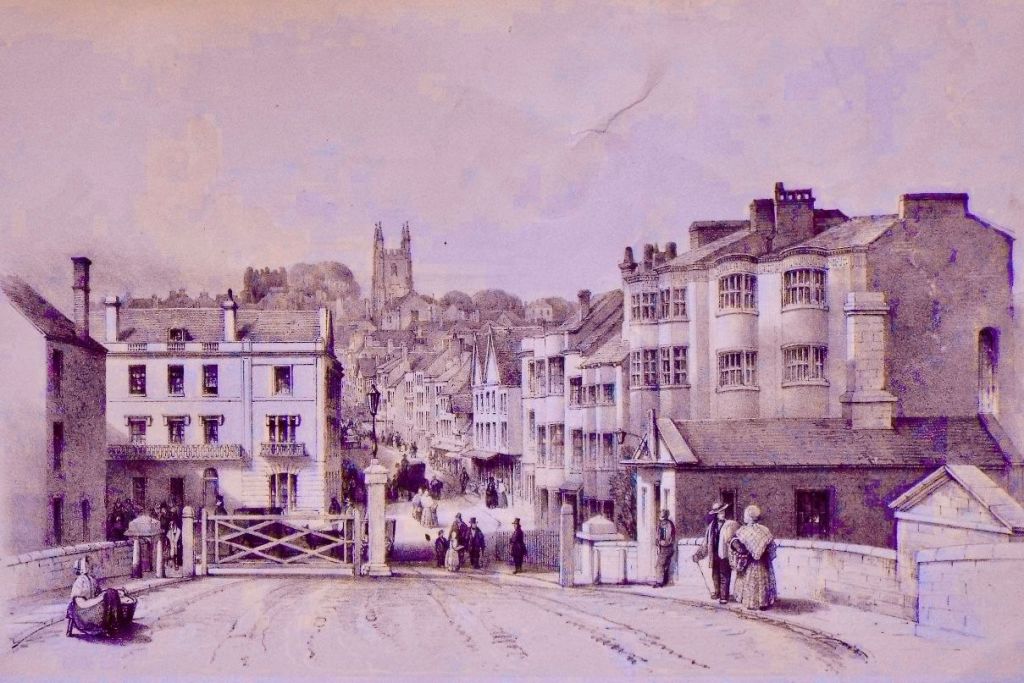

On Wednesday 29 October 1856, a group of fishermen saw Joshua Stanley’s body floating in the River Dart, not far from the bridge at Totnes in Devon. They pulled him out of the water onto St Peter’s Quay and then carried the corpse to the New London Inn. It was there that the inquest began a few days later.

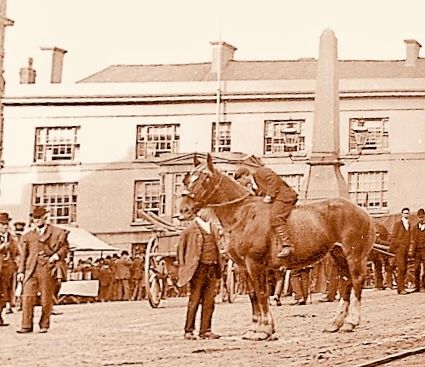

Joshua was well known in the district as the leader of the Romany Gypsy camp near Bowden, about two miles south of Totnes.

The first report in the Exeter & Plymouth Gazette claimed that Joshua attended the Totnes horse fair on the Tuesday, went drinking with his sons, apparently quarrelled with them and then threatened to drown himself. But Joshua had a great zest for life, so the idea of suicide was very soon discounted. By the weekend, it became clear that he had been strangled and then thrown into the river. This came as a shock to everyone because Joshua was known to be a strong and muscular man, as confirmed by the autopsy.

His wife Rhoda Cooper was asked to identify the body. A dark red line around the neck had been produced by the tortuous twisting of his neckerchief during strangulation, one of his eyes had been blackened, and some marks over the eye were thought to be the result of a blow to the head. Rhoda told the coroner that, when she raised Joshua’s eyelid, a few tears then mixed with drops of blood and flowed out onto his cheeks, which she took to be some kind of oracle, a sign that he recognised her from beyond.

Rhoda explained that Joshua was a decent husband whose last act had been to buy a pony for her so that she could ride with a pony and trap in her advancing years. She also said that Joshua left their caravan for the horse fair on the Tuesday morning, returning briefly in the afternoon to drink some hot grog. That was the last time that Rhoda saw her husband alive.

The eldest son Thomas Stanley was questioned at length at the inquest. Joshua was indeed out drinking in Totnes that day with his sons, in the Oxford Arms, so the early speculation about a family altercation still seemed plausible. It turned out that Thomas stayed in the pub with his cousin (one of the Hicks family) until the early hours, following which the two of them were put to bed there by the landlord in order to sleep it off.

Thomas last saw his father at about seven in the evening. The publican confirmed that Joshua had left the premises about then, adding that Joshua stood in the passage outside for some considerable time talking to a stranger who was respectably dressed.

After a one-week adjournment, during which time the borough constables made further inquiries, the Coroner and his jury heard that Joshua was next seen at about eight in the evening, in the New Walk in Totnes, about an hour after he left the Oxford Arms. A man in a velveteen jacket apparently ordered Joshua to follow him, which eventually he did. It looks as though Joshua was reluctant to do this at first, as he told a lad to whom he was talking at the time that it could easily end in a fight. Joshua was next seen on Totnes Bridge shortly after midnight by the keeper of the toll gate, Mr Davis, who recalled a particularly noisy gathering on the bridge on that day. In fact, he was fairly sure that Joshua was involved in an angry exchange about a horse deal. The last witness was a Mrs Mitchell, a nurse who was attending a feverish patient nearby. With the windows wide open, she heard groans about two in the morning followed by a splash in the water, whereupon she looked out to see a stout man dressed in dark clothes and a distinctive hat running towards the Dartmouth Road.

Robbery was ruled out as the motive. Joshua did not carry a pocket watch, his son said, and his loose change of three shillings and six pence was still in his pocket. As it happens, he also had with him a parcel containing the arsenic that he used for destroying rats for local farmers, and a worthless money order for the considerable sum of £105, drawn on a failed bank in Bath. Unfortunately, the tale behind that bounced cheque was not revealed at the inquest.

The only resolution to this sorry story is that, the following year, a man named Thomas Nation was hanged for an unconnected murder in the city of Wells, and it was rumoured that he was the likely killer of Joshua Stanley.

Thomas Stanley, the son who was questioned at the inquest, emigrated to America the next year with his wife Betsy Cooper. They crossed the Atlantic on the ship Kangaroo, arriving in New York in July 1857, together with Thomas’s brother Matthew Stanley, Matthew’s wife Martha Broadway, a likely sister Sophie Stanley (the widow of James Small) and a sister-in-law Isabella Cooper (the widow of a deceased brother named Joshua after his father). Together with their numerous children, the Stanleys were amongst a large party of Romanies on the Kangaroo, namely the Hicks, Buckland and Cooper families, who all quit the south west of England at that time.

Rhoda Cooper died in Somerset in 1868 and most likely did not travel to America with her children after her husband’s murder, even though a further two sons (William and Valentine Stanley) and another daughter (Betsy Stanley) were already there. Valentine Stanley is thought to have made an exploratory trip in August 1851 on the Yorkshire with Misella Cooper, in the company of Josiah and Onnar Boswell. After marrying back in England, Valentine and Misella emigrated permanently in 1854, travelling on the City of Manchester together with Betsy Stanley and her husband James. The youngest son William Stanley and his wife Phoebe Broadway had arrived in New York on the brig Josephine in September 1851, at the beginning of the Romanichal (British Romany) exodus of the 1850s.

NOTE

Joshua Stanley 1784-1856 was the great grandson of Hercules Stanley c1680-1725, whose younger brother Peter Stanley c1710-1779 was my six times great grandfather.

References

Death of ‘Old Stanley’ the Gipsy, Woolmer’s Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, Exeter, Saturday 1 November 1856

The Funeral of Joshua Stanley (the Gipsy King), The Western Times, Saturday 8 November 1856

Suspected Murder, The Exeter Flying Post & Trewman’s Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser, Thursday 13 November 1856

Murder of the Gipsy King, The Western Times, Saturday 15 November 1856

Murder of the Gipsy King, The Exeter Flying Post & Trewman’s Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser, Thursday 27 November 1856

Murder of the Gipsy King, The Western Times, Saturday 29 November 1856

The Murder of Stanley, the Gipsy King, The Exeter Flying Post & Trewman’s Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser, Saturday 29 November 1856

Execution of Nation, The Wells Journal, Saturday 25 April 1857

Links to related posts

The Romany Family at Claremont. Another look at the paintings and drawings of Sarah Cooper and her extended family made by the then Princess Victoria, and the related entries in Victoria’s diaries.

The Benefactor. The story of Alice Ayres and her family. Alice was a great granddaughter of Samuel Ayres whose extensive Romani vocabulary was documented by the East India Company translator John Staples Harriott at the Romany camp in Froyle in Hampshire in the early 1800s.

Leave a comment