Keywords: Argie, Bargie; Pub crawl, Downfall; Keeper’s Daughter, Fetch the Water; Athenaeum, Carpe-diem; Lumps of Coal, Down the Hold; Joe and Ben, Last Boatmen.

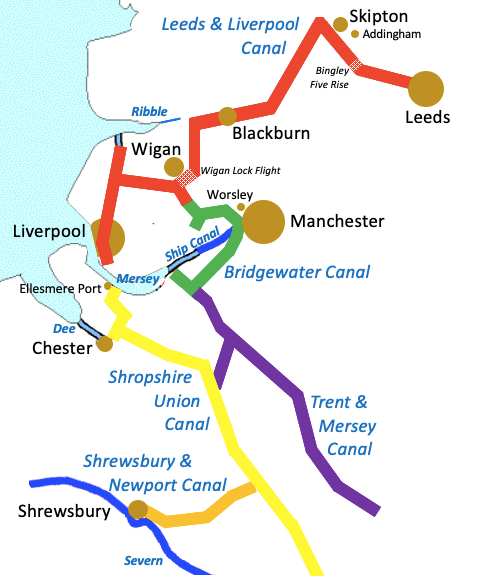

The six stories that are recounted here took place in 1847, 1848, 1850, 1861, 1877 and 1888. Each is based on a true account, or at least as true as the tale that was in the papers at the time. The stories are intertwined, as they relate in one way or another to the canals that link Manchester to Liverpool, Leeds and elsewhere. Also, with the benefit of hindsight, a kind of family tree (more like a labyrinth) falls into place as one generation follows another.

8th October 1847: Argie-Bargie

On 8th October 1847, two boatmen were brought before the Wigan magistrates by the lock keeper at Ince-in-Makerfield. The boatmen were Hugh Yates and William Bottomley, and they were charged with creating a disturbance on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal between 11 am and 12.30, for which they were fined five shillings each. It seems that they were both intent on getting their own barge into the lock first. The stand off lasted an hour and a half and developed into a proper argie-bargie, as it were.

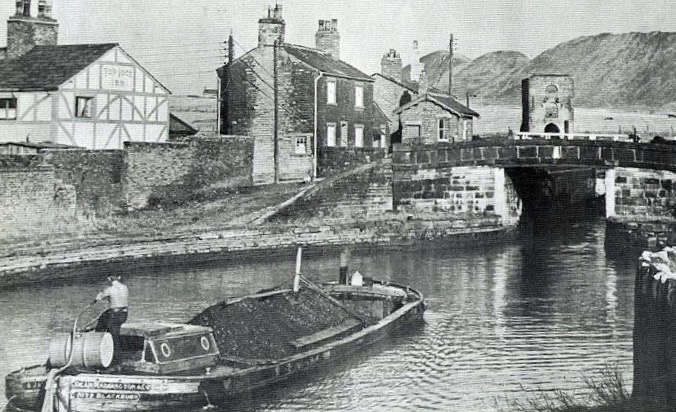

It is not straightforward picturing a scene like that back before there were photographic records, although the artists from that time can help a little. There were covered narrowboats on the canals by then — Turner roughly sketched one back in 1808, quite short in length, with a suspended canvas cover, and pulled by a horse across the aqueduct that takes the Trent & Mersey Canal over the River Dove. The wider barges that were designed initially to carry bulk cargo about at the docks were also in use on inland waterways before that time — in 1827 Constable drew two men loading from a farm cart into the holds of such a boat, which again was relatively short in length. Interestingly, there is a study of the Leeds & Liverpool Canal in about 1850 — by an unknown artist — that shows two laden barges near Wither Grange. We can only wonder if they too were striving to be first into the next lock.

Barges on British inland waterways (detail only, clockwise): Unknown artist, Leeds & Liverpool Canal, c1850; John Constable, The Stour, 1827, V&A; Joseph Turner, The Trent & Mersey Canal, 1808, Tate.

Missing from these (somewhat arcadian) drawings is any sense of the high volume of traffic on the canals by the late 1840s. Indeed, it is said that there were over one thousand working boats operating on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal at one point. Each colliery had its own fleet of coal barges, and the canal company itself operated countless boats of its own together with stabling for hundreds of mules and horses.

The lock keeper

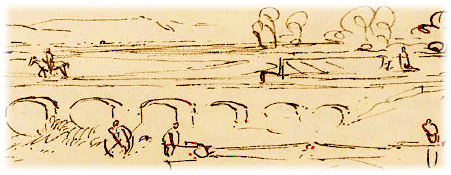

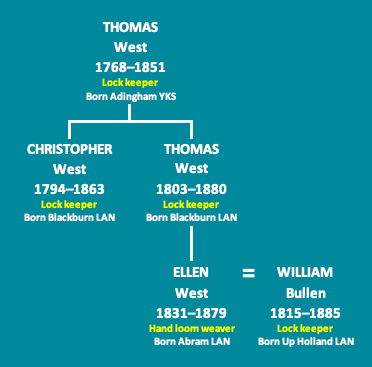

The lock keeper at Ince-in-Makerfield may well have been Thomas West who, although coming up to retirement, was the occupant of one of the four lock houses on the extensive flight of 23 locks that takes the Leeds & Liverpool Canal down from Aspull to the Wigan Basin. Six years earlier, when the 1841 census was compiled for the township of Ince, Thomas was recorded as the resident keeper in the tied cottage at Lock 8 together with his second wife Margaret Oliphant.

By the time of the hearing at the magistrates’ court in 1847, Thomas had reached the advanced age of 79. It looks as though his eldest son Christopher West took over the job in the following year, moving up then from Winwick with his own family. By 1851, they were all living together in the same lock house, including the ‘retired lock keeper’ Thomas West then aged 83.

Of the four lock houses, the first was by Top Lock at Aspull, the next on the canal bank at Lock 8 where Thomas West lived, and the third near Rose Bridge where Walter Bromley was the resident keeper (Rose Bridge Lock House also fell administratively within Ince, so there is always the possibility that Walter rather than Thomas may have been the unnamed keeper mentioned in the news report). The fourth lock house was in Wigan itself, beside Henhurst Bridge where the old road to Ashton-in-Makerfield (Chapel Lane) still crosses the canal to this day.

The area known as Makerfield was first recorded in the Domesday survey as 600 square miles of woodland. The villages of Ince-in-Makerfield and Ashton-in-Makerfield were established there in the middle ages, long before the arrival of industry and the canals. Thomas was not from Makerfield however, nor Wigan. He grew up in Addingham near Skipton in rural Yorkshire, and left the land there in 1790 to work in a cotton mill in Blackburn, some time before he found employment on the canals.

By 1790, when Thomas moved from Yorkshire to Blackburn, the Leeds & Liverpool Canal Company had built the reaches at the two ends of their planned waterway, both about 35 miles long — from Leeds to Skipton in Yorkshire and from Liverpool to Wigan in Lancashire. The next sections to be completed ran from Skipton to Accrington (1804), then from Accrington to Blackburn (1810), and finally from Blackburn to Wigan (1816). It would fit the story very nicely if, in 1810, Thomas and Walter had joined the Leeds & Liverpool Canal Company as two of the navvies who actually constructed the last section of the canal, the job taking them literally step by step from Blackburn to Wigan.

Whatever happened, by the 1820s Thomas West and his family were living in the mining community of Abram near Ashton-in-Makerfield. They must have moved from there into the keeper’s house on the Wigan flight at some time in the 1830s.

16th August 1848: The Gingham Bag

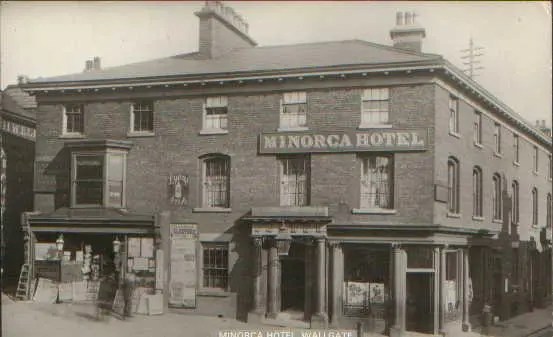

On the morning of Wednesday 16th August 1848, William Bullen — another of the lock keepers on the Wigan flight — went to the Minorca Inn on Wallgate with an acquaintance named John Holden. As John had no money, William had agreed to stand him a drink or two. Luckily, William could afford to do so at that time — he was thirty three years old, in work and still single. Originally from nearby Up Holland, he lived in the keeper’s cottage beside the Top Lock at Aspull. The day out in Wigan did not end well for his companion John Holden however. He appeared before the magistrates a few days later, charged with stealing from William.

Aerial view of part of the Wigan lock flight on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal (left), with past and present views of the lock keeper’s house at Top Lock (right) where William Bullen lived.

William kept his money in a bag made from gingham, probably with the characteristic checked pattern that is known today (striped gingham was woven in the early days but was less common by then). He had £9 in gold sovereigns with him on that Wednesday morning, along with £3 in half crowns, 10 shillings in sixpences and some pennies as well. According to Margaret Knowles, one of the women serving at the Minorca Inn, the two men came in together and had several glasses of whisky, which were paid for by William. Margaret explained in detail to the Police Court how William pulled “a brown and white bag out of the inside pocket of his coat, from which he took some silver,” to which she added “the next time I served them, he paid me in copper.” The gingham bag certainly looked weighty, she recalled.

The Minorca Inn on Wallgate, Wigan (later the Minorca Hotel)

Margaret Knowles also told the magistrates that John Holden had tried to make a bet with one of the other drinkers at the Minorca even though, as it turned out, neither had any money. She remembered John saying in passing that “If I have not, my friend has.” William had fallen asleep on a bench in the bar by then, but he woke up and bought another round of drinks. About ten minutes later, the two went out of the Minorca’s back door and down King Street.

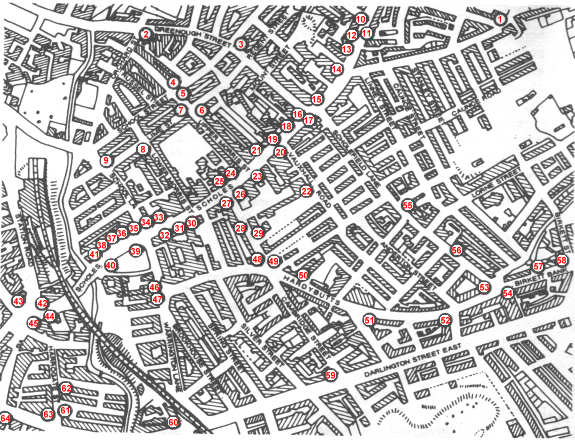

William and John then visited several other public houses. They made their way towards the area around Scholes, with its high number of beer houses, and just before four o’clock in the afternoon they found themselves in the White Hart Inn in Wellington Street.

This early map of Scholes (at wiganworld.co.uk) shows the great number of beer houses that had opened in the 1800s. The White Hart Inn is no. 28.

The publican at the White Hart was Joseph Gore. According to Joseph’s wife Sarah Gore, William paid for two glasses of ale on arrival there, but he soon fell asleep in the kitchen. The publican’s son Thomas Gore, who was in there at the time, told the court that John Holden finished off William’s drink after downing his own and then tried to get a servant girl to bring ale, bread and cheese on credit. She refused, but it looks as though the publican must have relented later on, at least in part, as he provided beer on the house to Holden about five o’clock.

The next thing to happen was that John Holden asked the publican’s son if he had any tobacco, which he did not. John’s reaction to this was to say “I’ll see if Bill has any.” Thomas Gore told the magistrates how he saw Holden “put his hand into Bullen’s left inside coat pocket” although “he did not see him pull anything out of the pocket, nor did he see him smoking any tobacco afterwards.”

John Holden eventually went into the tap room. The barmaid in there was Margaret Bragg, and she told the Police Court that she poured Holden a pint of ale for which he “tendered her sixpence for payment.” Another witness in the tap room was James Hodgkinson, a weaver, who said that Holden actually “pulled two sixpences out of his pocket” to pay for his pint. Soon afterwards, John left the Minorca Inn and made his way to Mr Mackenzie’s, where he paid for twopenny worth of gin, the court heard.

William Bullen woke up at about six o’clock in the evening, but it was only on his way home that he realised that his money had gone. He told the Police Court that “he had known the prisoner for years and never knew anything against him” and that “he had no recollection of what passed at Gore’s before he fell asleep.” On the day itself, it looks as though the police became involved after William returned to the Minorca Inn to look for his gingham bag. PC Fisher eventually apprehended John Holden in the Market Place at about eight o’clock in the evening. When searched, he was found to have with him “sixpence in silver and twopence in copper.”

On the bench at the Police Court were Joseph Acton, the Mayor and later a Whig member of parliament, and another magistrate named Richard Fegun. The final witness to appear before them was Mrs Mary Wigans of the Wheat Sheaf Inn on Wallgate. She was going through the Mesnes at about half past seven when she saw John Holden half way between Mesnes Lane and Hallgate. He was looking into a hedge, she said, and he did so for quite a while.

After Mrs Wigans had given her evidence, a group of seven people (including Joseph Gore from the Minorca Inn and another man named William Melling) made their way to the place where John Holden had been seen. A brown and white gingham bag was found by Melling shortly afterwards, and inside it was all the money except for five shillings.

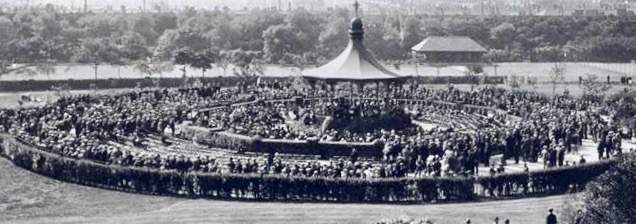

The Mesnes bandstand was built in the 1870s, when Mesnes Park was developed. There was a colliery on the site previously. It was near here that the gingham bag was recovered in 1848.

It certainly would be a fairytale ending if the additional five people who went in search of the gingham money bag happened to be the remaining witnesses for the prosecution — the weaver James Hodgkinson, Joseph Gore’s wife Sarah and their son Thomas, and the barmaids Margaret Knowles and Margaret Bragg, particularly as they had ended up restoring nearly all of the missing money to William. But the law does not work like that. The magistrates placed John Holden on bail and committed him for trial by jury at the next Borough Sessions, for the theft of £12 7s.

As it happens, there was a storybook ending of sorts. Although eleven witnesses were called at the trial, which took place three months after the Police Court hearing, “a searching and pointed address” by the defending Counsel persuaded the jury to find John Holden “Not Guilty“.

kith and kin

Six years after the regrettable pub crawl, William Bullen married Ellen West, the third generation of her family to live by the canal. Her grandfather was the Thomas West whose eldest son Christopher West had taken over as the lock keeper at Lock 8. That job went next to Thomas’s youngest son, also named Thomas West, who was Ellen’s father.

Before taking over from his father and his brother as the keeper at Lock 8, Thomas West junior was employed by the Leeds & Liverpool Canal Company as a canal labourer. He continued to live in the mining community of Abram to begin with, where Ellen West grew up with one sister and seven brothers, six of whom went down the local pit as coal miners. Perhaps the expectation was that the seventh brother, Thomas’s youngest son, might join the Canal Company. In fact, he went in a quite different direction and became a chartered accountant in Liverpool.

Ellen and William Bullen stayed in the cottage at Top Lock well into the 1870s when William was appointed as a Canal Agent, moving then into the Chapel Lane Lock House down at Lock 22. This was not far from a small and unremarkable wooden jetty (later demolished) where colliery wagons were unloaded into waiting barges, and which became better known as the apocryphal Wigan Pier that was celebrated first in music hall jokes and then by the writer George Orwell.

Three of the old keepers’ cottages today: Top Lock Cottage, with its canal-side toll booth on the corner (at Lock No. 1). Rose Bridge Lock House, recently renovated (at Lock No. 16). Chapel Lane Lock House (at Lock No. 22).

6th November 1850: The Lock Keeper’s Daughter

On Wednesday 6th November 1850, just before half past six in the evening, another Ellen West opened the door of the lock keeper’s house at Lock 8 and walked towards the canal to get a can of water. She was eleven years old, and a younger cousin of the Ellen West who went on to marry William Bullen. Her stepmother was probably inside Canal Bank Lock House at the time with the younger children, and her father the lock keeper Christopher West was out. As she walked towards the canal, Ellen saw a man named Barton, who was there with another named Even Kershaw. She asked if she could cross the towpath and fill her can up before they towed their boat past with their horse on their way up to Top Lock.

Having filled the can with water, Ellen then went back into the house. Soon after this, a coal barge captained by James Ingleby approached the next lock from the other direction, on its way down to Wigan Basin. The barge was the Earl, which belonged to the Earl of Crawford, the owner of the extensive shale and coal mines at Haigh Colliery (the business became the Wigan Coal and Iron Company a few years later). The mate on the barge was John Preet, who remained on board while James Ingleby walked over to wind up the paddles and fill Lock 7.

Barton heard the spindle turning and the paddles lifting, and quickly made his way by foot to the top gates. He asked James Ingleby, the captain of the Earl, to stop what he was doing and not fill the lock. This turned into an argument and, according to Barton, James Ingleby then struck him. A man named Thomas Heyes, who was returning home from work along the towpath, heard someone say “I’ll make you pay for that.” On the Earl, John Peet heard a cry of “Help me, help me,” followed by the ominous sound of something plunging into the water.

Both men (the passer-by Thomas Heyes and the mate John Peet) then ran to the spot to see what was happening. Barton explained to them that James Ingleby had fallen into the canal but had not come back up to the surface. Kershaw, who had joined the group of men at the lock side by then, told Barton to go to the keeper’s house at Lock 8 to get the search rake so that they could try to locate James Ingleby under the water and pull him out. However, given that Christopher West was not at home, his daughter Ellen had to run and fetch him.

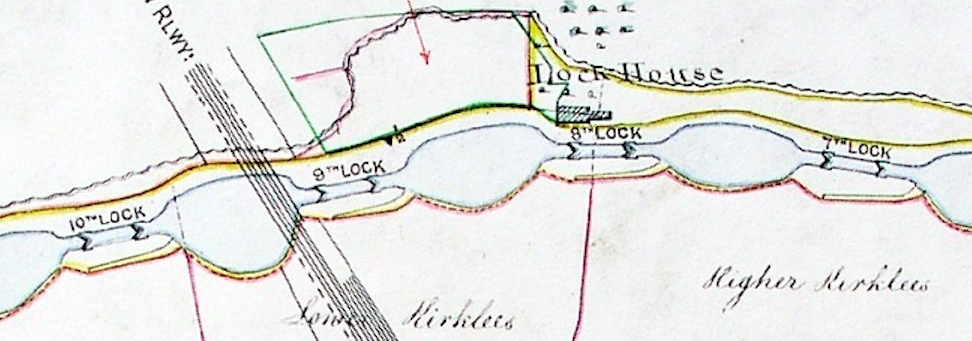

Locks 7 to 10 at Kirkless, written then as Kirklees (1827 Canal Survey map)

At the same time, John Peet went off to find the barge captain’s son, John Ingleby, who was also a boatman and was further down the flight at Lock 10. When they arrived back, they found Kershaw and Barton feeling around for James Ingelby with a boat shaft, without success. Thomas Heyes was also still there and looking around the canal, when suddenly he called out “He’s here.” John Ingleby took the shaft from Kershaw and Barton, and pulled out first his father’s hat and then his jacket and waistcoat. All of them must have realised by then that John had been submerged for too long.

The lock keeper arrived while this was going on. Grappling under the water with his rake, Christopher West searched out the drowned man and pulled him onto the bank of the canal. Not long after that, a narrow fly-boat in the service of the Canal Company carried the body to the Rose Bridge Inn.

Sergeant France of the county constabulary was at Ince-in Makerfield when he received the news about the events at Lock 7. It was half past nine in the evening by then, but he went out in the dark in search of Kershaw and Barton who had set off northwards on the canal. The Sergeant headed straight for Chorley to check that the two men had not already passed through there, and then made his way back down the towpath towards the Wigan locks. Kershaw and Barton were intercepted on the canal at Adlington, which is about three miles to the south of Chorley. The two men were charged with causing the death of the captain of the Earl by pushing him into the water. They were then held in custody until the inquest, which took place at the Rose Bridge Inn three days later. At the end of the hearing, the Coroner concluded that “as there was no person there at the time but the prisoners, there was no evidence to commit them.”

The chiseled lock number on a stone slab in the wall of Lock 8

In retrospect, it is not too difficult to imagine the lock keeper’s daughter looking out at the stonework as Lock 8 filled and emptied, closely watching Dickensian England ascend and descend before her very eyes, and then float away — not only getting a measure of the tough men who transported the coal and for whom the canal provided a well-earned livelihood, but also the Victorian villains who lived on the water on the fringes of society.

making tracks

As it happens, Christopher West’s daughter Ellen did not stay there for too long. She married a corporal in the 14th Hussars in 1862, and moved away — the Hussars were posted to Edinburgh that year, and then to Ireland, and after that to India.

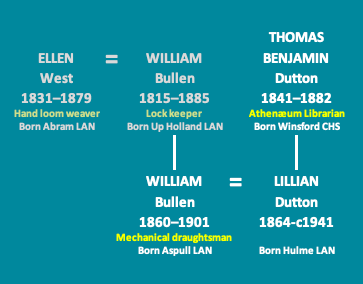

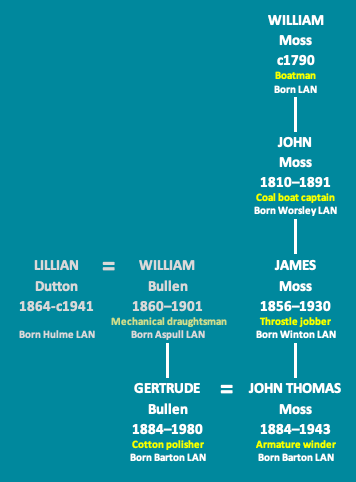

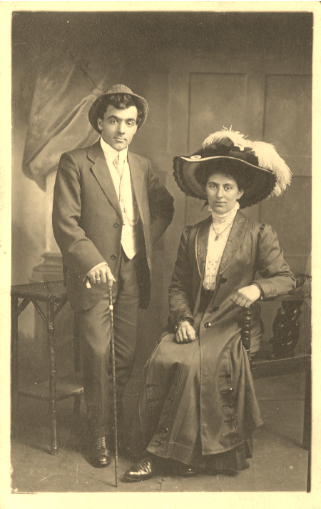

The other Ellen West, the daughter of Thomas West, only decamped as far as Top Lock, as already mentioned. She and William Bullen brought up one son and six daughters in the lock house there. The son was also named William Bullen, just like his father and his grandfather before him. Eventually he too made tracks and became a mechanical engineer’s draughtsman in Manchester, where he married Lillian Dutton, as shown below.

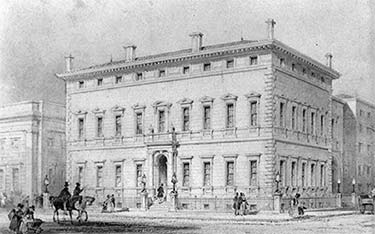

The next story concerns Lillian’s father, Thomas Benjamin Dutton, who was the librarian at the Manchester Athenæum. His was a very different way of life, working in Princes Street in the city centre, where the Athenæum Society was located in the first and finest of Manchester’s elegant Renaissance style buildings. It was at meetings in this building (and at the Free Trade Hall) that the Manchester Ship Canal scheme was developed. In the circumstances, the organisers of those meetings were very lucky to have the use of the Manchester Athenæum as a venue. A few years earlier, it was nearly razed to the ground.

24th April 1873: The Fire at the Athenæum

On Wednesday 24th April 1873, early in the morning, a serious fire broke out in Manchester Athenæum in Princes Street. A large ventilating gas lamp had set fire to the woodwork. The library was greatly damaged by the fire and 20,000 volumes of books were completely destroyed.

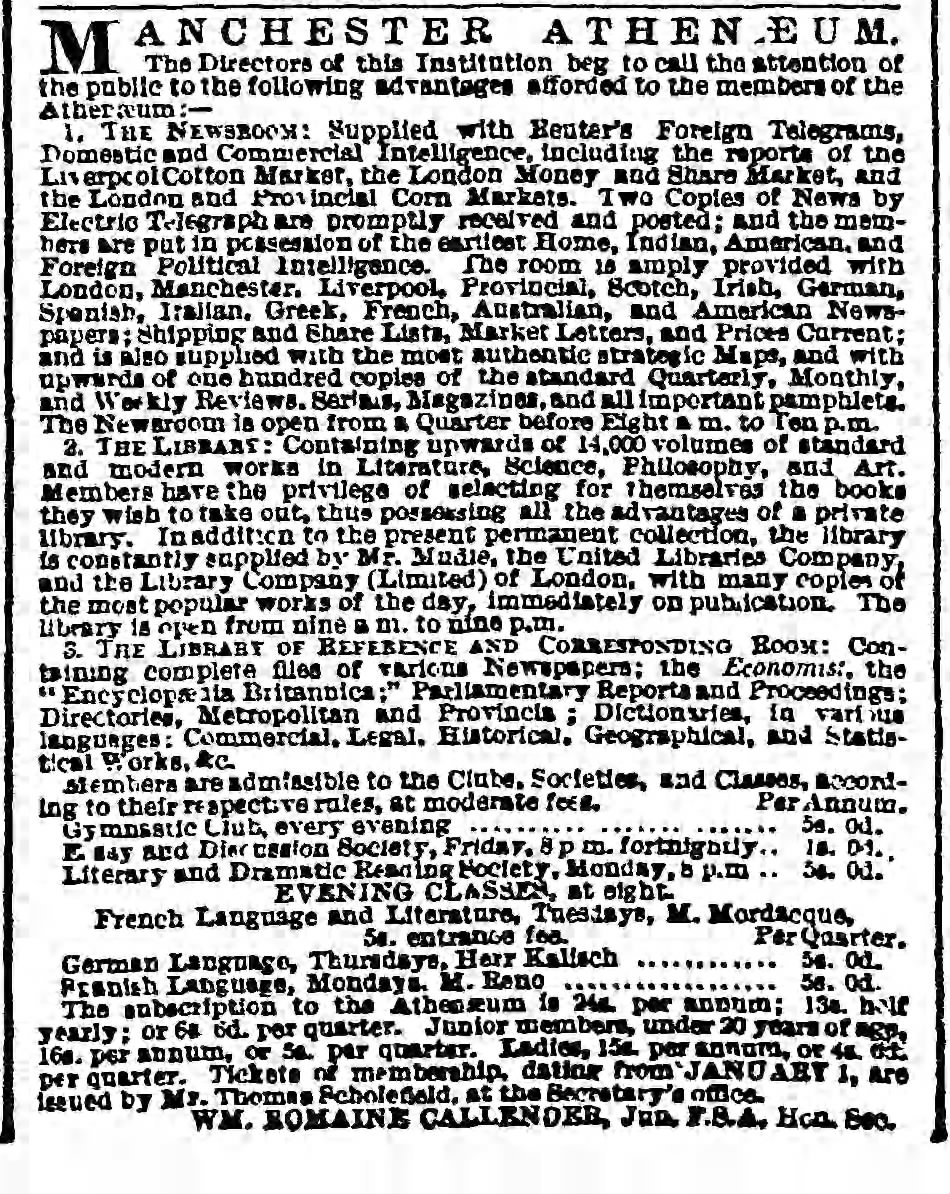

The librarian Thomas Benjamin Dutton had been at the Manchester Athenæum for more than ten years by then, having started there as a young man. Each day he was greeted by the bold inscriptions across the frontage, which tell us that the imposing building was erected in 1838, explicitly “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT AND DIFFUSION OF KNOWLEDGE” (today the same building forms an integral part of the Manchester Art Gallery, linked by a glass atrium). In its time, the Manchester Athenæum was a relatively progressive intellectual Society, meeting the specific needs and interests of those in trade and commerce in the city (at an annual subscription of 24s), offering a fee reduction to students and apprentices (16s), and admitting women long before the social norms started to catch up (regrettably, this sense of open-mindedness is rather tarnished by the fact that membership rights for females were far more limited).

Things had started well — Disraeli and Dickens spoke there in the 1840s. However, by the time that Thomas Dutton began working at the Athenæum, the main room originally intended for the library was occupied by the City Bankruptcy Commissioner who had to be eased out during the 1860s so that the Society could meet the demands of its increasing number of members. Shortly before the fire, the total membership had grown to 2,600 and, in addition to the well stocked library, there was a Coffee Room, a Chess Room, a Smoking Room, a Billiards Room and a well furnished Gymnasium, plus a News Room with Reuters telegrams and British and foreign newspapers. The News Room had become particularly busy, so Thomas developed an adjoining quiet area for the growing number of magazines and periodicals, as a dutiful librarian would.

There were some detractors nevertheless. For instance, the Bishop of Manchester spoke of “a slight flavour of suspicion” that the Athenæum’s “literary department was rather neglected in comparison with its culinary, gymnastic and other attractions.” The Bishop’s presumptuous wording seems as arrogant now as it surely was at the time, reflective of a snooty attitude towards people ‘in trade’, a mindset that was still present even in Manchester of all places. Not surprisingly, he went on to talk down “the study of trade technicalities” and to decry “utilitarian education” — all in a speech to the apprentices and students at the Athenæum! In much the same vein, the press claimed elsewhere that the Schiller Anstalt (the cultural centre of Manchester’s large German community) was somehow of higher quality, as signalled by its higher membership fees — even though its resources were far more limited in scope.

Interestingly, Thomas was the son of a joiner, his brother a ship’s carpenter and his two sisters a cotton weaver and a dress maker; they grew up together in Wharton in Cheshire, then in Broughton and then in Hulme, which makes his trajectory towards the centre of Manchester’s aesthetic life quite remarkable for those times, but very fitting. He went on to oversee the restocking of the library after the fire. The insurance claim took a year to settle, by which time the first 2,000 volumes had been replaced. In January 1875, a “Grand Soirée” was held at Manchester Free Trade Hall to celebrate the completion of reconstruction. A few years after that, Thomas’s health deteriorated and he died in 1882. The Courier spoke of his dedication to the Manchester Athenæum, his “urbanity” and his “powers of organisation,” which leaves a lasting impression.

the ship canal

During Thomas’s last months, the regular meetings held in the Athenæum to develop the proposals for a Manchester Ship Canal brought together representatives of each ward in the city. The main arguments were that the cargoes of ocean-going vessels could be brought directly into the city, that a large canal could carry much more produce per year than the existing canals, and, when considering the alternative, that the costs of canal transport were a fraction of the costs of rail transport. The Suez Canal had been open for ten years by then, so a plethora of detailed evidence was made available (for instance, the maintenance cost of Suez worked out then at 2½d per ton, compared with 5p per ton on ordinary canals). And so the persuasive reasoning continued. A meticulously organised campaign was launched to gain public support and, although stalled at first by opposition from the Port of Liverpool and from local landowners (the Trafford family), the Manchester Ship Canal Act was passed in 1885 on its third passage through Parliament.

Queen Victoria opened the Ship Canal on 21st May 1894, by releasing water from the locks near Trafford Wharf. She was escorted to the formalities by the 14th Hussars, who had just returned from India, and her diary entry for that day provides the following account:

“Reached Manchester at 4.30 … I had an escort of the 14th Hussars. We drove first to Albert Square … The Square is a fine one with a statue of dearest Albert under a canopy … We then went on to the Municipal School of Art … & from there to the Trafford Wharf, having stopped on the way at Old Trafford … We embarked on the ‘Enchantress’. I sat in the stern of the ship, which was rather a draughty place, under an awning … We then steamed slowly to the Mode Wheel Docks, where I declared the Canal & Docks open by opening the large lock … This done, the ‘Enchantress’ returned to the Trafford Wharf, where I re-entered my carriage & drove to the Exchange Station …“

As it happens, the Mode Wheel Docks are just upstream from the place where Thomas Benjamin Dutton was living at the end of his life in 1882, at Barton-upon-Irwell. This is where the innovative swing bridge was built to carry the Bridgewater Canal over the new Ship Canal in a moveable aqueduct, replacing the old stone aqueduct that crossed the River Irwell there in Thomas’s day.

Queen Victoria at the opening of the Manchester Ship Canal in 1894. The 1761 aqueduct that previously took the Bridgwater Canal over the River Irwell. The Barton Swing Bridge aqueduct, rotated through 90° to let ships pass.

Thomas’s daughter Lillian Dutton continued to live in Barton-upon-Irwell after she married William Bullen, and their daughter Gertrude Bullen grew up there. Gertie (as we knew her) was born in 1884, and went on to marry Jacky Moss who was also from Barton. Gertie and Jacky were ten years old when the Manchester Ship Canal was opened nearby, living then as they did in Shaftesbury Street and King Street, Barton. They would each have seen the barges being towed high up across the old stone aqueduct before that, and the two of them were no doubt amongst the early witnesses when the hydraulic steam engines first powered the new moveable aqueduct through its ninety degree turn.

the throstle jobber and the armature winder

Jacky Moss’s father James Moss was employed as a ‘throstle jobber’ in a cotton mill in the vicinity of Barton-upon-Irwell, and Jacky went on to work in a local velvet dyeworks, becoming a finishing machine foreman there in his twenties. Later, he moved to the Metropolitan-Vickers heavy engineering works in Trafford Park as an ‘armature winder’.

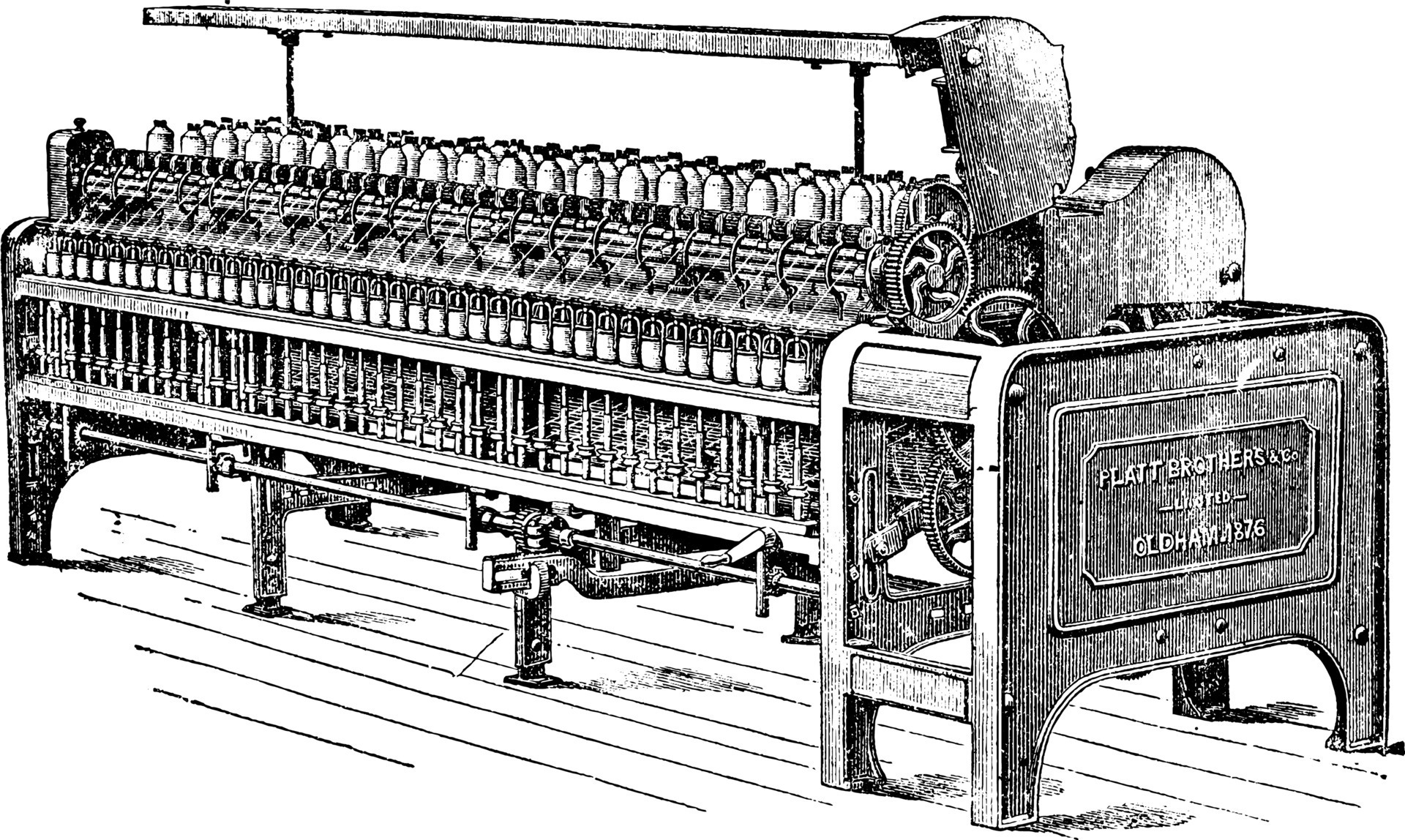

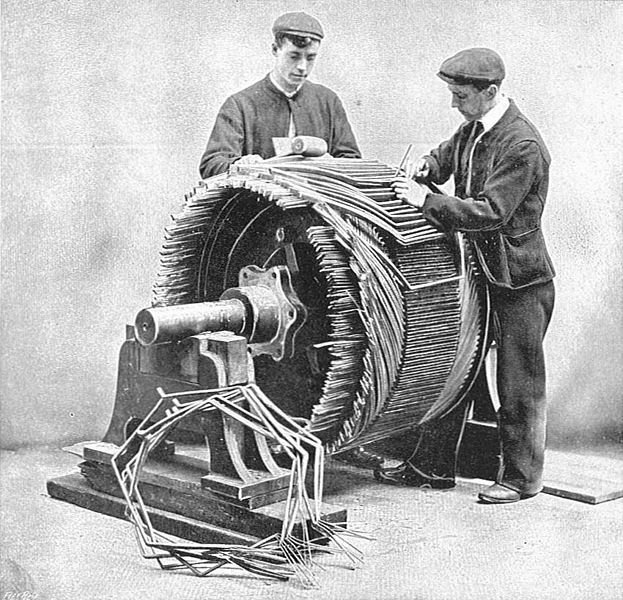

A throstle spinning machine, 1876. Armature winders in the early 1900s.

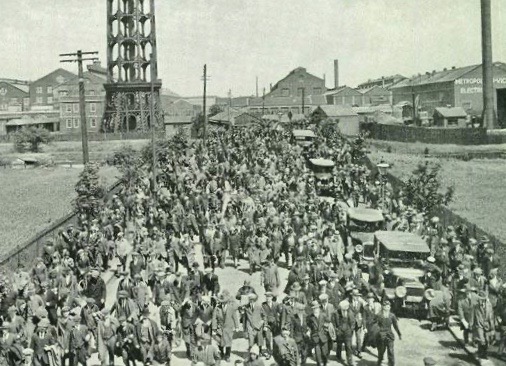

These jobs with their fascinating titles evoke two very different eras. The ‘throstle jobber’ attended to the continuous-action cotton spinning machines of the late nineteenth century, powered initially by steam that was generated with the coal brought in from the Lancashire coalfields (a throstle is the old name for a song thrush, and the machines apparently sounded like the thrush’s song). The ‘armature winder’ on the other hand built coils for twentieth century transformers and generators. These could be of considerable size, and the production at Trafford Park included marine turbines, jet engines and large-scale electrically-driven pumps like those that replaced the original hydraulic engines in the Barton Bridge power house. Construction of the Trafford factory was started about 1900 by the American Westinghouse company, who were attracted to the site by the completion of the Ship Canal — two firms (Vickers and Metropolitan) took over the Westinghouse business during WW1. As shown by the images below of production inside the MetroVick factory and of workers going home for the day, the scale of operations was colossal in all senses.

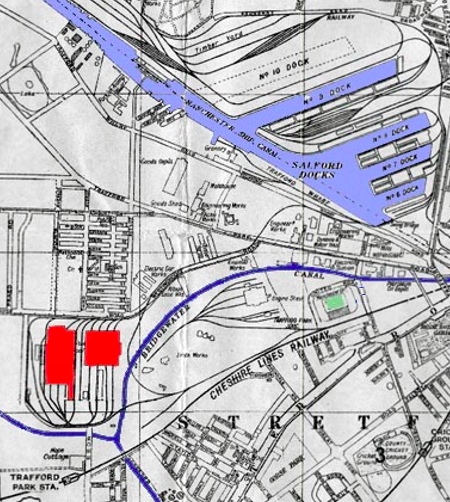

Metropolitan-Vickers archive images. Below. Map showing the proximity of the factory (in red) to the Bridgewater Canal and the Trafford Wharf at the end of the Manchester Ship Canal.

To reconnect more fundamentally with the canals, however, we only have to go back two generations to Jacky Moss’s grandfather, John Moss (1810-1891), who was a coal boat captain.

John Moss was born in Worsley, right by the Bridgewater Canal, where his father William Moss had been a boatman before him in the early 1800s. The Duke of Bridgewater owned the mines in Worsley, and the canal was built initially to ship his coal directly into the centre of Manchester, through an underground canal network for some of the way. When it opened in 1761, the Bridgewater Canal was said to be the first true canal in Britain, that is to say the first not to follow the path of an existing river. By John’s time, it had been extended both westwards from Manchester to the Mersey Estuary and northwards from Worsley in the direction of Wigan, connecting there with the Leeds & Liverpool Canal — and that is where we find John Moss at the beginning of 1877.

24th January 1877: The Coal Boat Captain

On Wednesday 24th January 1877, at about half past twelve at night, the coal barge ‘Francis’ captained by John Moss was moored at the township of Lydiate on the Leeds & Liverpool Canal. The barge belonged to the Wigan Coal and Iron Company, and it was carrying a load of cannel coal from the Haigh colliery. This type of bituminous coal was also known as candle coal or shale coal.

It is not clear where John was at the time, whether he was asleep on board or perhaps elsewhere. Two police officers, Sergeant Waddilove and Constable Rigby, were on duty on the opposite bank when they saw a wooden narrowboat coming slowly towards them from Liverpool, drawn by a horse and with the captain standing at the prow. It was one of the fly-boats belonging to the Leeds & Liverpool Canal Company, which ran a scheduled service delivering goods up and down the waterway, day and night. As soon as the fly-boat reached the coal barge, the captain stepped across from one to the other and began pushing some large blocks of cannel coal onto the gunwale of his own boat as it passed by. When the fly-boat had almost passed the coal barge, he stepped back and then manoeuvred the pieces of coal into a hold next to the cabin.

The Leeds & Liverpool Canal at Lydiate

The police officers followed the boat to the next bridge before boarding. Sergeant Waddilove said “Well, you’ve been helping yourself to yon cannel.” At first, the captain William Benson claimed that he had not left his boat since Old Bob’s bridge, three-quarters of a mile away, but he then resigned himself to his fate. He was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment at Ormskirk Police Court, all for six large pieces of cannel coal, weighing 122lbs and worth 17 pence at that time.

John Moss did not have to say much at the hearing. It seems odd that the Wigan Coal and Iron Company pursued a case involving only six blocks of coal worth 17 pence, but it turns out that they had just uncovered systematic coal theft on the canal — out of 117 boats sent to Liverpool with coal in December 1876, 17 were weighed, and about 1.82 tons was missing from each boat on average, worth £40 4s 5d altogether. The company calculated that this would imply a grand total of nearly £278 for all 117 boat loads. Such detailed calculations are understandable, but bewildering in the circumstances of this particular case, like taking a sledgehammer to crack a nut. Let’s hope that, with all that effort, they managed to track down more than 17 pence worth of stolen coal.

lost in the labyrinth

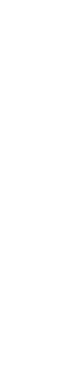

So far, a line has been followed from West to Bullen to Dutton and Moss, and — very luckily — newspaper articles from their times have been able to tell us a little more. The final and retrospective interconnection starts with Jacky and Gertie’s daughter Vera Moss whose first marriage was to Bert Witkiss, the two of them having met when they were working as a telegraphist and a clerk for the railways. In a way, their employment is quite symbolic, given the railway’s displacement of the canals — by the late 1930s, the days had long gone since canal barges shifted as much freight around as railway trucks. That kind of equilibrium belonged to the 1800s, and is reflected in an interesting way in an earlier generation of the Witkiss family — that is, while Bert’s grandfather James Witkiss was the first to work on the railways, as a wagon examiner and wheel tapper in Shrewsbury and Whitchurch, his two cousins Joseph and Benjamin Witkiss were still making their living as boatmen on the canals that linked Shrewsbury to Ellesmere Port and Manchester, and also to Wolverhampton and Birmingham.

Benjamin and Joseph Witkiss were brought up on the barges. Their mother was Emma Witkiss from Shrewsbury in Shropshire, and their father Edward Underhill from Womburne near Wolverhampton (the sons mainly used their mother’s surname, although not always). In 1861, a few months before Benjamin was born, Emma, Edward and seven year old Joseph were living on the ‘Myrtle’ at Wolverhampton, which was carrying 20 tons of iron that day. Ten years later, in 1871, the two brothers were together on the barge ‘Land’s End’ on the Shrewsbury and Newport Canal. The elder brother Joseph Witkiss continued to live on the barges with his own family into the 1900s — he captained the ‘Nellie’, the ‘Bessemer’ and the ‘Martha’, amongst others, the baptisms of the children telling us that they were sometimes moored in the Ellesmere Port barge dock, at other times down near Wolverhampton, and once (in 1891) halfway along the Shropshire Union Canal at Middlewich.

The narrow locks on the Shropshire Union Canal. Two old photographs of barge families, about 1900.

As for the younger brother Benjamin Witkiss, he became a resident of Oldbury in Birmingham and a boatman there … which takes us to the last story.

26th August 1888: Boisterous Boatmen

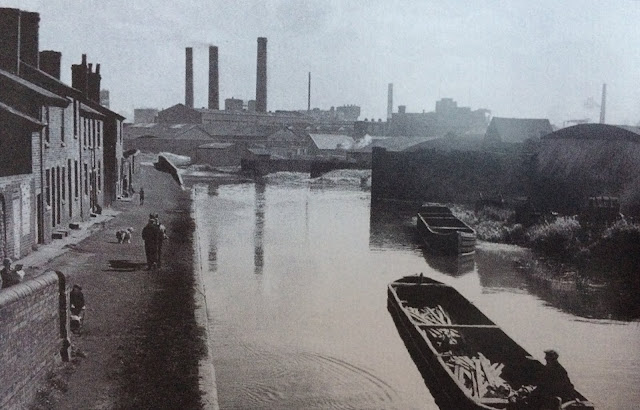

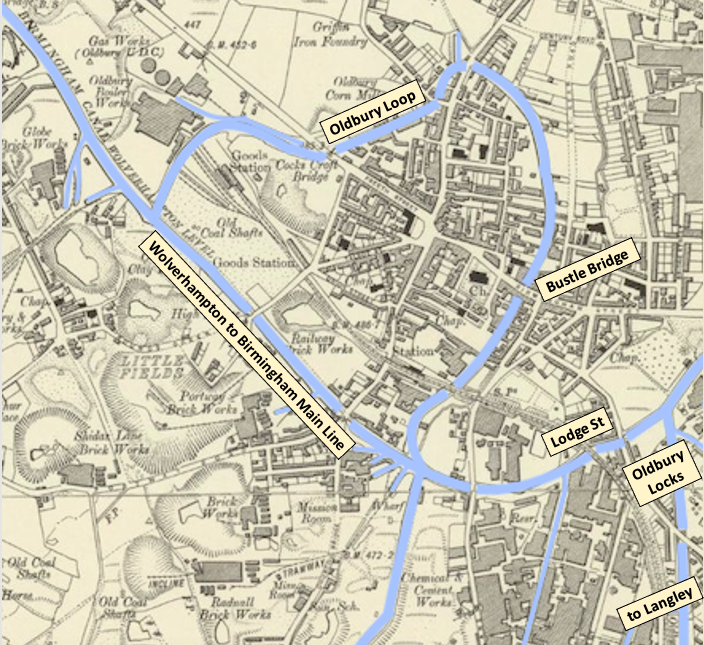

On Sunday 26th August 1888, Benjamin Witkiss and three other boatmen were at Langley near Oldbury, where an intricate system of feeder canals, branch canals and fan wharves served the iron foundries, brickworks and heavy industries of the Black Country. The four men (Benjamin Witkiss, James Jelf, Charles King and George Folley) were neighbours in Lodge Street, which is next to the Main Line Canal from Wolverhampton to Birmingham and not far from the Oldbury Loop — the Loop was actually part of the canal’s original route when it meandered through the Black Country staying at the same level.

Bustle Bridge on the Oldbury Loop. Approaching the Loop entrance on the Wolverhampton to Birmingham Main Line Canal. Canal terraces in Oldbury. Below. Map of the Oldbury Loop (Benjamin Witkiss lived at Lodge Street).

Langley is just over a mile to the south of Lodge Street, just past the Oldbury locks off the Main Line Canal. It was a summer’s day and the four friends were larking around on a canal bank there, throwing one another into the water. Although one of them could not swim, they still tossed him in and then jumped in themselves to help him keep afloat, splashing about and generally making a din. But it was a Sunday, and such things were frowned upon. Police Constable Bayliss was summoned by the residents, and when he arrived at the canal side he charged the four boatmen with disorderly behaviour.

Ten days later, on Wednesday 5th September, the Birmingham magistrates fined them 2s 6d each, and the Daily Post reported briefly on the hearing under a headline that captured the moment: “BOISTEROUS AMUSEMENT”.

So, what were they really, these boisterous boatmen? Unruly, vociferous, or maybe just refreshingly unrestrained…

The canals were built at the height of the industrial revolution. There must be many more stories out there of the people who worked the boats and kept the locks, of those in the family who chose a different path elsewhere, and those who just lived nearby looking on.

Sources

Argie-Bargie: “Caution to Boatmen” The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser Saturday 9 October 1847 p8.

The Gingham Bag: “Police Court: Robbery from the Person” The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser Saturday 19 August 1848 p5. Also Saturday 11 November 1848 p8 (Not Guilty).

The Lock Keeper’s Daughter: “Man Found Drowned” The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser Saturday 16 November 1850 p5 Also Saturday 9 December 1865 p3 (The Wigan Murder). Saturday 18 August 1866 (Guilty)

The Fire at the Athenæum: “Destructive Fire at the Manchester Athenæum” The Manchester Evening News Wednesday 24 September 1873 p2. Also Monday 15 December 1873 p4 (The Schiller Anstalt), Thursday 2 December 1875 p2 (The Bishop of Manchester), The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser Wednesday 3 June 1874 p6 (Reconstruction of the Athenæum), Saturday 12 December 1874 p1 (Grand Soirée), Saturday 10 June 1882 p14 (Thomas B Dutton), Saturday 2 December 1882 p14 (Manchester Ship Canal).

The Coal Boat Captain: “Stealing Coal from a Canal Boat” The Ormskirk Advertiser Thursday 1 February 1877 p3.

Boisterous Boatmen: “Boisterous Amusement” The Birmingham Daily Post Wednesday 5 September 1888 p8.

Jacky Moss and Gertie Bullen

Leave a reply to Veronica Crowe Cancel reply