Part 1 – The Cooper Portraits

Based on the informative articles by Sarah Murden in All Things Georgian (2016) and the helpful contextual discussions by Janet Keet-Black (2006), Eric Trudgill (2010), Jeremy Harte (2016, 2023), Alan Wright (2017) and David Cressy (2020), Victoria’s portraits of the Cooper family and her related diary entries are investigated again below. Two questions are addressed here. First, is there a likeness of Isabella somewhere amongst Victoria’s drawings, to complement the existing portraits of Mary, Sarah, Eliza and Phillis Cooper? Second, can the six children pictured with Sarah be matched one by one to the names given by Victoria in her diary? Part 2 will follow later, and will try to piece together more of the jigsaw.

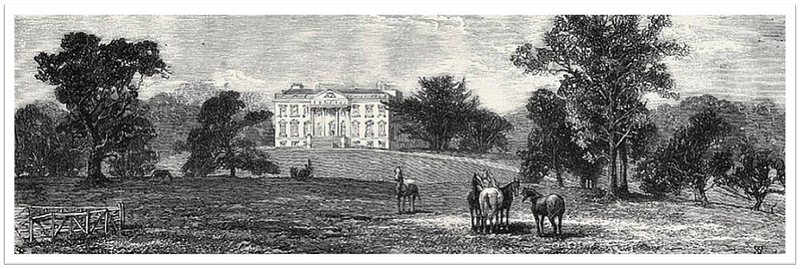

Six months before she became Queen, Victoria was greeted by two members of a Romany family who were camping at Claremont in Surrey. This was on Saturday 3rd December 1836, while the seventeen year old Victoria was out walking in the grounds by the Portsmouth Road. The two were Mary Cooper and her daughter Sarah, and further encounters with them seemed to kindle in Victoria a considerable affection for the two women.

Over the following month, Victoria continued to pass by the encampment on her daily walk. She had conversations with the women on at least eleven occasions before they moved on . Victoria wrote in her diary about each of those encounters and recorded some vivid impressions of the Romany family. A hint of familiarity (‘our Gipsy friends‘) began to creep into the diary, or perhaps it was a mixture of fascination with the entrancing winter visitors and a growing awareness of their vulnerability. On 11th December, Victoria’s diary entry was:

“We saw our Gipsy friends peeping out of their frail abode of canvass. They certainly are a hard-faring race.”

Victoria went on to describe the Cooper family members in greater detail in the following days, but she said little more about the campsite itself in her diary. We only know that the tents were on the opposite side of the Portsmouth Road, so maybe in the shelter of a clump of trees on the common land there. Looking at contemporary paintings for insight, it is evident that Gypsy dwellings became a subject of some interest to artists about that time. While earlier painters such as Gainsborough had focused on the weathered faces and colourful appearance of the people themselves, there are several nineteenth century studies of Romany encampments in Britain that can help us to imagine the scene, and to picture the type of bender tent that was then the norm.

The five women who were sleeping under canvas on the edge of the Claremont estate were Mary Cooper, her daughter Sarah Cooper, and three daughters-in-law: Eliza Lee, the wife of Mary’s youngest son Matthias (generally known as Matty); Philadelphia Smith (known as Phillis), the wife of Mary’s son Leonard; and Isabella Smith, who was not identified by name in the diary but was the wife of Mary’s son Nelson.

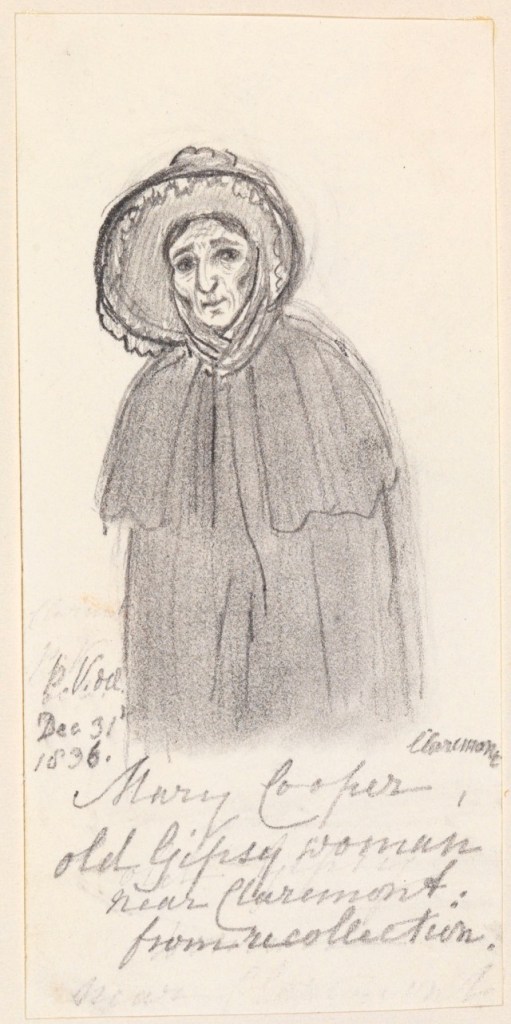

Mary Cooper

Mary Cooper is thought to be Mary Buckland, the second wife of Henry Cooper White. When Victoria walked by the camp on Saturday 17th December 1836, it proved to be a particularly memorable day as Mary came out of her tent with a newly born grandson under her shawl to show to the passing royals. The baby was just one day old, and this— together with the straightforward and kindly manner of the Romany women— appears to have had quite an effect on the seventeen year old Victoria.

Towards the end of the Cooper family’s stay, Victoria included a brief description of Mary in her daily diary entry:

“She has a singular clever but withered countenance herself, with not one grey hair, and is very respectful and well bred in her manner.”

On the whole, the substance and tone of Victoria’s comments seem to reflect her high regard for Mary. Victoria drew a particularly sympathetic portrait the next day, in which Mary looks both astute and dignified. The work has the following inscription: Mary Cooper, old Gipsy woman near Claremont, from recollection. It was dated Dec. 31st 1836 by the Princess Victoria, and marked P.V. del. to indicate that she drew the picture.

Sarah Cooper

On 3rd December, the day when their paths first crossed, Victoria briefly recorded in her diary that she had met

“two Gipsies, an old and a young woman”

adding quite zestfully about Sarah that

“the young one was beautiful and so picturesc!”

The emphasis achieved by Victoria’s single exclamation mark is especially telling! At one level, Victoria may simply have been delighted to find a new and exotic subject to sketch and to paint. However, the lifestyle that she observed and the pleasant demeanour of Sarah and her family certainly gave Victoria reason to think far more deeply about them. The word at the end of her sentence, which is generally spelled as ‘picturesque’, certainly conveys the idea of artistic appeal. It is difficult to say what Victoria actually had in mind. Was it simply something bland like the ‘kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture‘, the definition of ‘picturesque’ offered by the artist Gilpin who was inspired by the exquisite landscapes of Capability Brown to start a lively debate a few years earlier on the concept of the ‘picturesque‘? Or was it some notion of alluring wildness, a more romantic view of the unconventional Romany way of life?

On the day after the diary entry, Victoria produced the first of her watercolour paintings of the Coopers, showing Sarah in a lustrous long red cloak and a chic black hat. The main part of the inscription in this case is: Gipsy woman near Claremont called Sarah Cooper. It was initialed P.V. in the usual way, dated Dec. 4th 1836, and again described as From recollection.

Sarah Cooper, by Victoria, dated 4 Dec 1836 ©

There is another closely related work in the Royal Collection. It is on a folded sheet of paper, undated and without annotation, and clearly of Sarah. She is seen wearing similar clothes to those above and facing forwards this time rather than in profile (on the other side of this watercolour is a small pencil outline of the face of an unnamed woman, to which we shall return later).

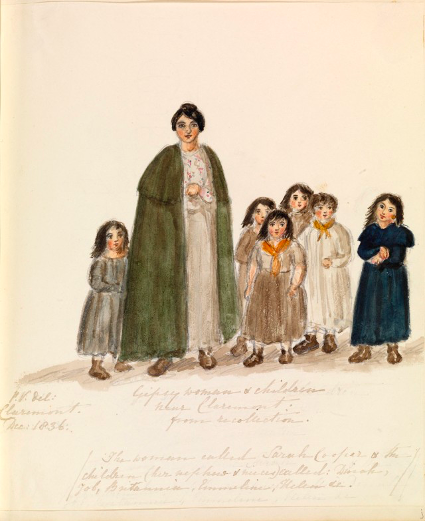

Just before the arrival of the newborn child, another noteworthy incident had made it into the diary involving Sarah and the children in the camp. On 15th December, ‘Aunt Sarah’ (as she was called from then on in the diary) brought six of her young nieces and nephews across the road and introduced them to the royal party. The walkers that day included Jane and Victoire Conroy, daughters of the family comptroller Sir John Conroy, together with Victoria’s governess Louise Lehzen. The scene was described by Victoria in her diary, as follows:

“As we were walking along the road near to the Tents, the woman who said she was called Cooper, and who is generally the spokeswoman of the party, stepped across the road from the tents, and as we turned & stopped, came up to us with a whole swarm of children, six I think. It was a singular, and yet a pretty and picturesc sight. She herself with nothing on her head, her raven hair hanging untidily about her fine countenance, and a dingy dark green cloak hung on one side of her shoulders, while the set of little brats swarming round her, with dark dishevelled hair & dark dresses, all little things and all beautiful children.”

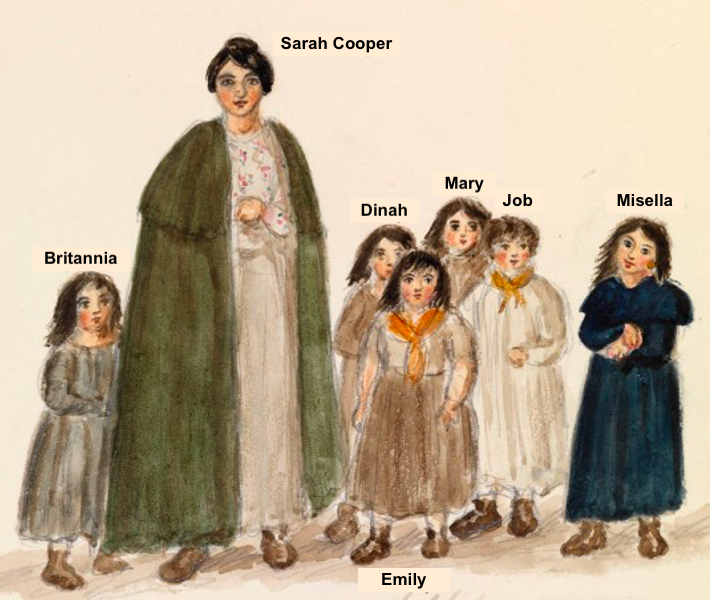

There is a watercolour by Victoria that portrays the ‘picturesc sight’ that day. It was prepared from memory and dated December 1836.

Sarah is standing with six young children, the picture accentuating her raven black hair and her long dark green cloak. The inscription this time is Gipsy woman and children near Claremont. From Recollection (The woman called Sarah Cooper and the children – her nephews and nieces – called: Dinah, Job, Britannia, Emmeline, Helen &c.). We shall return to this painting later, and find out more about the various children involved.

There are two more full-length watercolours of Sarah. In the first, Sarah is shown in a long and patterned cotton dress with her crimson scarf around her neckline, and holding a large black bag. In the other (for which a preliminary sketch also exists), Sarah is again wearing her green cloak and her black hair is covered in part by the crimson headscarf. Each of the two works is inscribed in the same way by Victoria, simply as Gipsy woman near Claremont called Sarah Cooper and dated Dec. 1836

Curiously, a much lengthier and richer description of Sarah appears in the diary after these watercolours were completed. The relevant diary entry was on 1st January 1837, the last day on which Victoria talked with the Romany family. It reads as follows:

“I never saw Aunt Sarah look more beautiful than she did this time; she looked so cheerful and she had so much colour; her countenance is a very peculiar one, and a most difficult one to draw from recollection, for there is so much mind and soul in it; she has a tawny complexion, a low forehead, finely pencilled but not arched eyebrows, beautiful, dark, expressive eyes with splendid eyelashes, a small high nose, high cheek bones, a projecting mouth, beautiful teeth, and a falling back chin; et pour comble de tout [and to top it off] raven black hair, over which she wore a bright crimson handkerchief fastened under her chin, as she almost always wears.”

Victoria then added

“I do so wish I could take her likeness from nature! What a study she would be!”

With these distinctive features in mind, Victoria completed a last painting of Sarah in Claremont on the following day. The wish confided to her diary (to paint Sarah ‘from nature’) did not materialise, so once again the work was produced from memory. The picture is inscribed in the usual matter-of-fact way by Victoria:

Sarah Cooper, Gipsy woman near Claremont from recollection, dated Jan. 2d 1837.

Sarah is in her green cloak and is wearing the crimson headscarf under her chin. Consistent with the characteristics newly entered in the diary, her forehead is marginally lower now, her eyebrows a little straighter, her nose quite small and the cheek bones quite high.

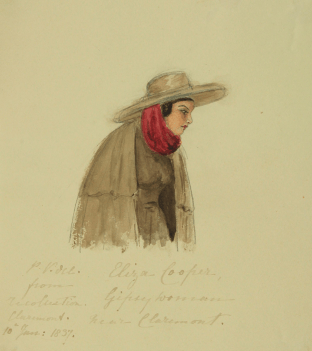

Eliza Lee

On 7th December 1836, a few days after the initial encounter with Mary and Sarah, Victoria met

“the same two Gipsies … accompanied by another very pretty one”.

The ‘pretty one’ was Eliza Lee, the wife of Mary’s youngest son Matty. As we know, the couple’s first child was born a week afterwards, on 16th December. Victoria mentioned Eliza’s good looks again two days later, saying that she has

“a most lovely face”.

Victoria went on to produce two watercolours of Eliza standing with Sarah. In the first of these, Eliza is facing forward and holding what looks like a metal milk pail in her hand while Sarah is looking away to the right. This time, the inscription reads Gipsy women near Claremont. From recollection. (The one in the red cloak called Sarah Cooper, the other, her sister-in-law called Eliza Cooper).This work was dated Dec. 10th 1836 by Victoria.

The painting on the right was dated Dec. 12th 1836, and it is perhaps the best of Victoria’s compositions at that time. Here, Eliza is seen carrying the rolled-up red cloak on her back with a bundle on top, possibly willow cuttings used for basket making. Sarah is wearing the ‘dingy dark green cloak’ and is peering to the left this time, standing back a little in a way that puts the spotlight on Eliza. Yet both paintings arouse the sneaking suspicion that Eliza was the more servile of the two and probably responsible for many of the chores, given the milk pail in her hand and the bundle on her back. Another tell-tale indicator in this regard is the peg apron that Eliza is wearing, which suggests that she also had laundry duties — interestingly, the apron partly conceals the fact that she was at the end of her first pregnancy.

We know that Victoria completed two more paintings of Eliza. One was finished nearly a week after the group had moved away — the portrait was signed and dated by Victoria on Jan. 10th 1837 with the inscription Eliza Cooper, Gipsy woman near Claremont. It looks as though the facial expression in this half-length portrait was taken from the painting below, in which Eliza is shown walking ahead of her mother-in-law.

This was on 15th December, shortly after the children had been brought out to meet the royal party. Victoria tells us about it in the diary, as follows:

“We had not proceeded far before we met the old Mother Gipsy, the pretty sister-in-law, and two other sisters-in-law…” .

In other words, it seems that Mary and Eliza were actually out with Phillis and Isabella at the time. Intriguingly, there is one additional person in the painting of Mary and Eliza, someone of about the same height who was sketched in very lightly on the right hand side (by tilting the screen or by zooming in, the ghostly silhouette of another woman should be just about visible…).

“The old woman called Mary Cooper, and the young woman (her daughter-in-law) Eliza Cooper. As I saw them on the 15th Dec. 1836.” ©

The sumptuous red cloaks worn by Eliza and Mary in this painting — and by Sarah in three other paintings — are particularly fascinating. Like some kind of dynastic regalia, the gowns seem to give the Romany women a real air of distinction. Many years later, the ethnologist Charles Leland mentioned similar red cloaks in The English Gipsies and Their Language. The book was published in 1873, and was based on conversations with Eliza’s husband Matty and, on occasions, with Matty’s younger sister Gentilla . Perhaps it was more than coincidence, and maybe they were still the family’s preferred attire when Leland later wrote about ‘two old fortune-telling sisters’ who would ‘expend on new red cloaks a sum which seemed … very considerable.’ In the paintings, the Cooper family’s red gowns certainly have that expensive look.

Phillis Smith

Victoria’s diary entry of 15th December tells us a little more about the ‘two other sisters-in-law,’ that each was carrying a baby in her arms. Victoria also noted that one of them in particular was ‘very pretty.’

There were three subsequent diary references in the same vein. On 17th December, one of the women was seen walking on the other side of the road, and Victoria wrote later in the day that she was

“very pretty though not the prettiest of the two”.

Similarly, on 28th December, Victoria recorded that she saw

“the least pretty of the two … in a shop in Esher.”

Finally, on 1st January 1837, Victoria learned one of their names from Louise Lehzen, which came up in an exchange with Mary . The name of

“the least pretty of the two sisters-in-law, she said, was Phillis”.

So it turns out that it was poor Phillis whose looks were ranked the least favourably by Victoria. Given the care taken by Victoria to note the identity of those she painted, we know that there exists a full-length painting of Phillis. It is inscribed Gipsy woman and child near Claremont. The woman called Phillis Cooper and the boy Nelson, dated Jan. 12th 1837. In the painting, Phillis is shown on the heath with her son Nelson, possibly picking up kindling given the time of year. Nelson seems to be biting into an apple.

Phillis Cooper and her son Nelson, by Victoria, dated 12 Jan 1837 ©

Isabella Smith

On 18th December 1836, Victoria wrote a detailed note about the ‘prettiest of the two‘ in her diary:

“She has a fine complexion, not much colour, small expressive eyes, a most lovely nose, and pretty mouth; she had nothing on her head, and her fine soft glossy black hair was parted with great care. She had a printed cotton dress on with a red & yellow handkerchief round her neck; she has a sharp, clever, but good-humoured expression and seems quite young though she has several children; she is the beauty of the whole set.”

Even though Victoria painstakingly recorded these defining characteristics in her diary, Isabella remained nameless in the diary and there is no painting of her in the collection. However, a number of pencil drawings exist, and amongst these there could be a potential candidate for Isabella’s likeness.

The first (left above) is the undated drawing on the reverse side of a folded sheet of paper that was mentioned earlier. The drawing shows a woman’s face in profile, and is described in the Royal Collection as A Traveller Woman. However, it looks more like a draft for the 4th December painting of Sarah (the one in which she is wearing her lustrous black hat), rather than a portrait of Isabella.

The sketch on the right above is from the edge of the watercolour in which Mary is walking along behind Eliza on 15th December (The old woman called Mary Cooper, and the young woman her daughter-in-law Eliza Cooper). This person was lightly drawn on the paper, but not painted. The image is enhanced here, showing a face slightly hidden by the border, and it looks like a preparatory sketch of Phillis rather than a portrait of Isabella.

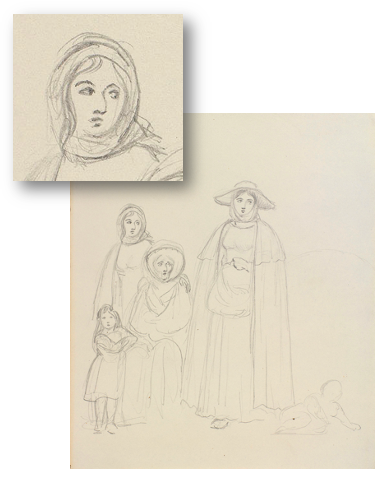

The drawing in the centre above is very lightly sketched in the background of one of the two full-length watercolours of Sarah (Gipsy woman near Claremont called Sarah Cooper), the one in which Sarah is wearing her green cloak. The face is similar to that in the larger group drawing reproduced below, which could be a rough draft for an abandoned painting. In both cases (the light sketch above and the group drawing below), the woman seems to be wearing a scarf or shawl as a head-covering, rather than a hat, which suggests that this may be a different person, and therefore a more possible likeness for Isabella. There is no annotation by Victoria on the group drawing, and therefore the individuals are not identified. We can see below that two younger women are shown standing, with Mary Cooper seated between them. A girl is leaning on Mary’s knee and a baby is just about discernible on the floor by the feet of the taller young woman. The Royal Collection notes online that the latter must be Eliza Lee, who is certainly dressed as she appears in the watercolours, with a wide brimmed hat and a peg apron. Perhaps the other young woman (her face is enlarged below) is the mother both of the crawling baby and of the girl who is resting against Mary Cooper, in which case this could be Isabella with her youngest child Dangerfield (then between one and two) and her daughter Britannia (then nearly four) or Emily (then five or six).

That would be a very pleasing outcome. However, there is also a chance that it might be another sketch of of Phillis, with her baby son Thomas (then less than one) and her daughter Dinah (then about nine) …

The Cooper Family sketched by Victoria, Undated ©

The Men

There are no paintings of the men at the Claremont camp. As it happens, the volume into which the Claremont watercolours have been bound also contains a number of paintings by Victoria of Spanish sailors and French fishermen. Victoria saw them at Ramsgate harbour during her two month stay there before moving to Claremont. So it is surprising in a way that she did not also try her hand at drawing the Romany men.

There is a diary entry that briefly describes Eliza’s husband Matty Cooper. This was on 20th December 1836, when Victoria wrote that

“No one was stirring about the camp except one of the men, I think he is the husband of the young woman, who was walking slowly along the road; he has a peculiar, handsome, dark Italian countenance & seems quite young.”

There is a more detailed description, again of a man with Italian looks, who was encountered in January 1837 after the tents had gone:

”We met in walking homewards a Gipsy and a boy both on horseback; the man was remarkably handsome and independent looking; had a grey hat, trousers and gaiters on, a green jacket and a bright red handkerchief tied loosely round his neck; he looked quite Italian like; the boy had a black beaver hat on with a pipe in his mouth.”

If the Cooper family members were still in the vicinity, the man may have been Leonard or Nelson, or an unrecognised Matty now on his horse and differently dressed , or even their older brother Frank who perhaps was camping nearby. The boy may have been a similarly unrecognised George, or one of Frank’s sons, but this is mere guesswork.

In much the same way as the detailed diary note on Sarah (1 January 1837) has the feel of an aide-mémoire for a painting to be completed later in the day, here again we can sense Victoria’s plan for another composition – the man’s hat would be grey, the jacket green and the scarf bright red. But it seems as though the plan did not materialise, as there is no such painting on record.

The Children

As mentioned earlier, Victoria noted the names of five children beneath the painting of Sarah with six of her nieces and nephews. The same list also appears in the diary entry on 15th December 1836. Speaking to Victoria’s governess Louise Lehzen, Sarah said of her two brothers’ six oldest children

“I am aunt to all these”

and then proceeded to name each of them. Victoria wrote later

“I remember only five; Dinah, Job, Britannia, Emmeline, and I think Helen. Britannia is a beautiful little large black eyed thing, with a dirty face who was wiped to be shown off. Sarah, then pointed to her own boy, called George, her only child, who was carrying another little nephew named Nelson, on his back.”

Victoria saw Dinah and Emmeline again two days later, when they were with Mary Cooper and the new born baby. She saw George once again as well, by himself on Christmas Eve.

Dinah, Job, Britannia and an Emily (rather than Emmeline) were indeed among Mary Cooper’s known grandchildren, as were Nelson and George who were not in the group of six as they were playing across the road. The diary also mentions two younger children, in their mothers’ arms at the time and therefore also not in the painting—these were Dangerfield who was born to Isabella and Nelson in 1835 (based on baptism records) and Thomas who was born to Phillis and Leonard in 1836 (based on census records).

There is no record for a Helen (or Ellen) in this generation of the Cooper family, and Victoria was herself uncertain about the name. However, Sarah’s two brothers had another daughter each who would have been there at Claremont. They were:

- Misella, known to be the eldest daughter of Nelson and Isabella; and

- Mary, the eldest child of Leonard and Phillis who went on to marry George.

Altogether, the likely family composition at the Claremont camp could have been as follows:

| Sarah 31 George 12 |

| Phillis 26 & Leonard 29 Mary 9, Dinah 7, Job 5, Nelson 3, Thomas 1 |

| Isabella 30 & Nelson 34 Misella 12, Emily 5, Britannia 4, Dangerfield 1 |

| Eliza 26 & Matty 25 Francis – born 16th December 1836 |

With regard to Victoria’s painting of the group of children, the above leads to the following tentative interpretation. Misella was the eldest girl (12), and therefore likely to have been the one wearing the more seasoned, dark blue dress. Mary (9) and Dinah (7) are likely to have been taller than Emily (5) and Britannia (4). As Victoria made special mention of Britannia in her diary, perhaps she is the girl standing closer to Sarah, on her right. The only boy there was Job (5), given that Thomas (1) and Dangerfield (1) were down the road with their mothers and George (12) and Nelson (3) were playing together away from the group.

Possible identities of the children in Victoria’s painting: Job was the only boy in the group, Misella was the eldest girl and therefore more likely to have been wearing the more seasoned dress, and Mary and Dinah were older and presumably taller than Emily and Britannia.

Part 2 (in progress) will again try to build on the informative articles by Sarah Murden in All Things Georgian (2016), and bring together further details about the various family members. One aim in particular is to document the respective ages of those who were camping at Claremont , in order to verify the family composition indicated above.

attachment

Locating the Camp at Claremont – a note on the possible site of the Cooper family’s camp, and the history and layout of the Claremont estate.

Acknowledgment

Thanks are due to the Royal Archive and the Royal Collection Trust regarding the reproduction here of the extracts from the diary transcripts and the copies of related paintings by Princess Victoria. These can be accessed directly at http://www.queenvictoriasjournals.org/ (the copyright holders are listed on the home page) and at https://www.rct.uk/ (all images from the Royal Collection Trust are the copyright of the Crown, and are marked © accordingly in the picture captions). Victoria’s original spelling is maintained in diary quotations and in her painting annotations, deferring to the handwritten original where necessary. I am grateful to Robert Dane Matthews, a descendant of Sarah Cooper, for insightful information about George and Mary, and to Di Stiff of the Surrey History Centre for making this study available to a wider audience.

Sources

David Altheer, The Guardian, Saturday 5 February 2011 (Refers to Victoria’s diaries)

David Cressy, Gypsies: An English History, Oxford University Press, 2020, 432 pages (Claremont pp172-174)

Jeremy Harte, “On the far side of the hedge: Gypsies in local history”, The Local Historian, Jan 2016 Vol 46(1) 27–46 (Claremont p28)

Jeremy Harte, Travellers through Time: A Gypsy History, Reaktion Books, 2023, 320 pages (Claremont pp63-65)

Janet Keet-Black, “Princess Victoria’s Gypsies”, Romany Routes, March 2006 Vol 7(6) 254–255

Sarah Murden, “Princess Victoria and the Gypsies”, All Things Georgian, Part 1: 6 December 2016 (Reviews Victoria’s portraits and her diary entries concerning the Cooper family), Part 2: 8 December 2016 (Pieces together further information about the Cooper family)

Albert Thomas Sinclair, American Gypsies, Bulletin of the New York Public Library, May 1917, reprinted August 1917 18 pages

Eric Trudgill, “William Cooper’s children”, Romany Routes, December 20101 Vol 10 (1) 21–24

Queen Victoria’s Journals Online (Victoria’s original manuscript and a typed transcript prepared for Lord Esher). The full set of transcribed journal entries relating to the Cooper family are also available on the website Romani.

Marina Warner, “Queen Victoria as an artist: From her sketchbooks in the Royal Collection”, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, June 1980, Vol 128, 421–436 (Overview of Victoria’s artistic activities)

Alan Wright, Their Day Has Passed: Gypsies in Victorian and Edwardian Surrey, Grosvenor House Publishing, Tolworth, 2017, 289 pages (Claremont pp106-107)

Works by Victoria (in order of appearance in the text, indicating the Royal Collection Inventory Number)

Mary Cooper, 31 Dec 1836, RCIN 980013.o

Sarah Cooper, 4 Dec 1836, RCIN 980013.g (in red cloak, in profile)

Untitled watercolour, undated, RCIN 980019.cb verso (probably Sarah Cooper, in red cloak)

Sarah Cooper with her nephews and nieces, Dec 1836, RCIN 980013.j

Sarah Cooper, Dec 1836, RCIN 980013.l (with black bag, in profile)

Sarah Cooper, Dec 1836, RCIN 980013.m (in green cloak, in profile)

Sarah Cooper, Dec 1836, pencil drawing, RCIN 980006.r

Sarah Cooper, 2 Jan 1837, RCIN 980013.p (in green cloak)

Sarah Cooper and her sister-in-law Eliza Cooper, 10 Dec 1836, 980013.h (Sarah Cooper in red cloak)

Sarah Cooper and her sister-in-law Eliza Cooper, 12 Dec 1836, 980013.i (Sarah Cooper in green cloak)

Eliza Cooper, 10 Jan 1837, RCIN 980013.q

Mary Cooper and her daughter-in-law Eliza Cooper, seen on 15 Dec. 1836, RCIN 980013.k

Phillis Cooper and Nelson, 12 Jan 1837, RCIN 980013.n

Untitled pencil drawing (A Traveller Woman), undated, RCIN 980019.cb

Untitled pencil drawing (The Cooper Family), undated, RCIN 980019.bu

Leave a reply to The Camp at Claremont – Stuart McLeay Cancel reply